The impossible stand of Vito Rocco Bertoldo —

48 hours, alone, against Tigers, grenadiers, and a German offensive racing for Strasbourg.

The Man the Army Didn’t Want

On December 8, 1941 — with Pearl Harbor still burning — Vito Bertoldo stood in a recruiting station in Decatur, Illinois, hands blackened with coal dust from the morning shift.

The Army doctor held up the eye chart.

Even the big letters blurred.

“4-F,” the doctor said. “Unfit for military service.”

It was the eighth time he heard those words.

Too blind.

Too dangerous.

A liability.

Friends called him Lucky Rocky, “lucky” to avoid the draft.

They didn’t understand.

Vito didn’t want safety.

He wanted purpose.

He chased recruiting stations across Illinois like a man possessed.

Springfield.

Champaign.

Chicago.

Always the same verdict.

Until one recruiter — behind on his monthly quota — finally offered pity disguised as policy:

“You can serve… but only as limited duty. MP or kitchen staff.”

Vito signed before the ink was dry.

He had clawed his way into uniform.

He didn’t care if he had to peel potatoes to do it.

The Wrong Man in the Kitchen

At Fort Leonard Wood, he trained beside men destined for Normandy and Anzio.

He struggled with marksmanship.

Glasses fogged. Lenses slipped.

Still, he volunteered for every miserable detail no one else wanted.

But he had a problem.

He didn’t shut up.

To the mess sergeant, he was a headache.

To the company commander, Captain William Corson, he was a chronic irritation.

A half-blind cook with too much fight and nowhere to put it.

In late 1944, with the war bleeding men faster than replacements could arrive, the Army bent its own rules.

Bertoldo was granted permission to deploy as infantry — officially still a messman, but cleared to “fight as needed.”

It was the first crack in the wall keeping him from the war he’d spent years trying to reach.

The German Offensive That Should Have Crushed Him

January 1945.

The 42nd Infantry Division — green, improvised, understrength — arrived in France just in time for Operation Nordwind, Hitler’s final attempt to break the U.S. 7th Army.

Two German divisions — the 25th Panzergrenadier and 21st Panzer, veterans of Kursk, Caen, Metz — crashed into American lines around the villages of Hatten and Rittershoffen.

Tigers.

Panzer IVs.

Half-tracks.

88s.

Thousands of infantry.

The 242nd Infantry Regiment was thrown into the path of the attack like a fire brigade plugging holes.

Company A took up positions in shattered Maginot Line pillboxes outside Hatten — ancient concrete tombs waiting to happen.

Inside them, men whispered about tanks crushing foxholes and entire squads disappearing under artillery.

It was, in every sense, a perfect place to die.

“Send the Cook. Good riddance.”

On January 8, battalion headquarters sent orders:

Three soldiers from each company to guard the Battalion Command Post in Hatten.

Corson didn’t hesitate.

“Send the cook,” he said.

“Good riddance.”

Guard duty at a CP wasn’t punishment — but it wasn’t combat either.

For Vito, who’d fought two years to get into the fight, it felt like exile.

He gathered his gear and walked into Hatten as night fell.

He didn’t know Company A was already being overrun.

He didn’t know tanks were rolling through the outskirts.

He didn’t know he was walking into the deadliest hours the division would ever face.

He only knew he was close — finally close — to real combat.

When the CP Fell Silent

Midnight.

January 9.

The ground trembled.

Engines growled.

Panzer silhouettes moved between houses.

Artillery smashed Hatten’s narrow streets.

Buildings folded.

Windows shattered.

The battalion staff realized they were seconds from encirclement.

They burned maps.

Smashed radios.

Prepared a retreat.

Then they looked at the nine men guarding the building.

Nine men to buy time for hundreds.

Bertoldo stepped forward.

“I’ll stay,” he said.

“Let me cover your withdrawal.”

A half-blind cook volunteering to stand alone against an armored assault.

They agreed because they were desperate…

…and because they had no idea what this man had inside him.

Dawn Over Hatten — One Man vs. a Panzer Division

4:30 a.m.

The last American footsteps vanished into darkness.

Vito dragged a .30-caliber M1919 machine gun to the entrance, braced it on rubble, and waited.

5:00 a.m.

A Tiger tank rolled past, its 88 sweeping the street.

He stayed still.

5:15 a.m.

Panzergrenadiers — hardened men from the Eastern Front — moved in loose formation, expecting nothing more than a few retreating Americans.

Vito stepped into the middle of the street.

Fully exposed.

And opened fire.

Ten Seconds That Changed the Battle

The first burst tore apart a squad before they even knew where the fire came from.

He swung left.

Another burst.

More men down.

Right.

Another.

In ten seconds, the German advance element was shredded.

That’s when the Panzer IV’s turret swung toward him.

He dove back inside as the shell obliterated the spot where he’d been standing.

The enemy assumed they were fighting a full American squad.

Vito dragged the M1919 to a window and fired again.

Two half-tracks arrived.

Twenty grenadiers dismounted.

He hosed them down.

The survivors radioed frantically:

“Heavy American resistance… multiple machine guns… strongpoint… impossible to dislodge.”

They had no idea it was one man.

Twelve Hours Alone

By 11:00 a.m., an 88mm round blasted into the room, throwing Vito across the floor.

His ears bled.

His nose dripped red.

His glasses were cracked.

He strapped the machine gun to a table with his belt, leaned it against the ruined windowframe, and kept firing.

When the barrel overheated, he urinated on it.

When ammunition ran low, he went to single-shot fire.

When Germans tried flanking, he shifted to another window.

He turned one building into a phantom platoon.

By nightfall, the illusion had saved the battalion.

His reward?

A new order:

“Retreat to the alternate CP.”

Vito:

“I’ll stay behind. I’ll cover you.”

Again, alone.

Day Two — Inside a Death Trap

January 10.

6:00 a.m.

The Germans launched their heaviest attack yet.

A Panzer IV.

A self-propelled 88.

Fifteen grenadiers.

Vito moved into a neighboring building to cover the CP’s flanks.

They fired an 88 from so close the muzzle blasted almost into the window.

The explosion knocked him across the room.

Shrapnel.

Blood.

Ringing ears.

He crawled back to the gun.

A German assault squad charged the stairs.

Vito cut them down.

Again they thought they’d silenced him.

Again he reappeared from a different window.

By noon, German officers committed an entire company to removing what they still believed was a fortified American stronghold.

It was still mostly one man.

Relief Arrives — and Finds a Legend

At 4:30 p.m., American forces from the 79th Division broke into Hatten.

Gunfire roared.

Buildings collapsed.

And somewhere inside the smoke, a single .30-cal fired its last belt in one long, defiant burst.

When the first U.S. soldiers entered the building, they found:

walls cratered

windows blown out

German bodies in heaps outside

the floor carpeted in thousands of hot brass casings

a battered, bleeding man slumped over a smoking machine gun

Master Sergeant Vito Rocco Bertoldo had been fighting for 48 hours without rest, alone more often than not, against armor, artillery, grenadiers, and one of Hitler’s last offensives.

The Aftermath — and the Medal of Honor

Investigators didn’t believe the witnesses at first.

The shell holes were too many.

The casings too dense.

The German dead too numerous.

“Impossible,” they said.

“No single man could have done this.”

But witness after witness confirmed it.

German prisoners swore they’d fought a full American platoon.

The truth shattered them.

It had been one half-blind cook with a machine gun.

A man the Army had rejected seven times.

A man who refused to leave a battlefield he’d finally reached.

When the 242nd Infantry Regiment entered Hatten with 781 men, only 264 remained three days later.

Two elite German divisions were rendered combat-ineffective.

Hitler’s last offensive in the west ground to a halt in those narrow streets.

Because one man held a doorway.

December 18, 1945 — The Blue Room

President Harry Truman stood in the White House Blue Room, reading the citation aloud while General Eisenhower looked on.

“…with extreme gallantry…

…guarding two command posts…

…against vastly superior forces…

…for more than 48 hours without rest…

…killing at least 40 hostile soldiers.”

When Truman finished, he shook Vito’s hand.

“You earned this,” he said quietly.

Reporters surged.

“What did you think of during those 48 hours?”

Vito answered softly:

“I was just trying to protect some other American soldiers.

I wasn’t trying to win anything.”

The Man the Army Didn’t Want — The Hero They Needed

He went home to silence and obscurity.

Helped veterans.

Served his community.

Lived quietly until his death in 1966.

Captain Corson — the officer who had sent him to CP duty to get him out of the way — read about the Medal of Honor in the newspaper.

His reaction was simple:

“Imagine my surprise.”

History is full of men the system almost missed.

Men told they weren’t fit enough, sharp enough, good enough.

Men who slipped through cracks and saved lives anyway.

But few changed the course of a battle — and an entire offensive — quite like the half-blind cook from Illinois who refused to go home without a fight.

Master Sergeant Vito Rocco Bertoldo.

The man who fought like an army.

News

How One Woman’s Torn Typewriter Ribbon Saved 3,000 Lives and Sank 4 Japanese Carriers in 5 Hours

THE WOMAN WHO SAW WHAT NO ONE ELSE DID How a torn typewriter ribbon cracked the code of the Imperial…

How One Farmer’s “Silo Sniper Nest” Killed 28 German Officers

The Silo Sniper How a Wisconsin dairy farmer climbed into a grain tower, rewrote the rules of counter-sniping in Normandy,…

This 19-Year-Old Was Flying His First Mission — And Accidentally Started a New Combat Tactic

How a 19-year-old Mustang pilot broke every rule in the manual—and accidentally reinvented air combat for the next eighty years….

How One Gunner’s “Suicidal” Tactic Destroyed 12 Bf 109s in 4 Minutes — Changed Air Combat Forever

March 6, 1944.Twenty-three thousand feet over Germany, a B-17 Flying Fortress named Hell’s Fury carved contrails through thin, freezing air….

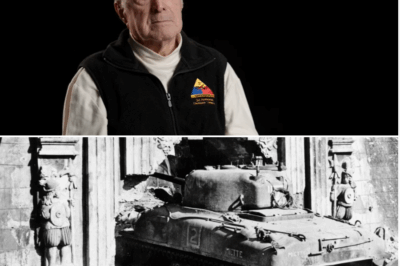

The Day a Loader Became a Gunner

What it felt like to move one seat over inside a Sherman—and see war for the first time through a…

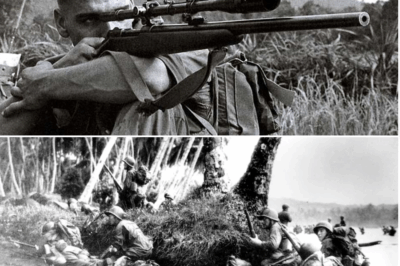

The Mail-Order Rifleman

How a state-champion civilian with a sporting rifle walked alone into Point Cruz—and outshot the Japanese Army’s best snipers. A…

End of content

No more pages to load