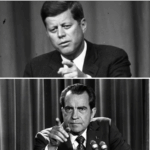

FEBRUARY 14TH, 1963 — THE SNOWFALL AT 20 BROAD STREET

2:15 p.m.

Lower Manhattan.

A black Lincoln Continental idles against the curb as snow drifts down through the steel canyons of Wall Street.

Inside the car sits the most powerful man on Earth.

President John Fitzgerald Kennedy.

Age 45.

Nuclear survivor of October ’62.

The avatar of American grace under pressure.

But he does not move.

He stares at the brass plate above the revolving door of 20 Broad Street, the name glinting through the snowfall:

Mudge, Stern, Baldwin & Todd — Attorneys at Law.

Nineteen floors above, in a corner office with a filtered view of the New York Stock Exchange, another figure waits.

Richard Milhous Nixon.

Age 50.

Former Vice President.

Former Cold Warrior-in-chief.

Now exiled to private practice after two of the most humiliating defeats in modern American politics.

He is waiting for the President.

But the President will not come.

He will not ascend the elevator.

He will not enter the law firm.

He will not shake the hand of the man who once shared a sleeping car with him on the night train back from Pittsburgh in 1947.

Because Kennedy believes Nixon has crossed a line no American statesman may cross.

And so begins one of the most quietly explosive encounters of the Cold War — a confrontation witnessed by no cameras, recorded in no official diaries, but which would shape the psychological architecture of two presidencies and alter the emotional DNA of American politics for a generation.

PART I — TWO MEN, ONE RIVALRY, AND THE FATE OF A GENERATION

They began together in January 1947, sworn in on the same day as freshman congressmen.

Nixon: the grinding, relentless striver

Kennedy: the luminous scion of wealth and myth

Two sons of World War II America, two opposing visions of Cold War leadership.

For years their relationship was a knife sheathed in velvet — rivalry wrapped in mutual respect.

Until 1960 shattered it forever.

Kennedy won the presidency by the width of a human hair —

0.17% of the vote.

Illinois by eight thousand ballots.

Texas by forty-six thousand.

Rumors of ballot-stuffing in Chicago and electoral sorcery in the Rio Grande Valley haunted Nixon like a fever dream.

And yet, when the Constitution demanded it, Nixon certified the electoral count with perfect decorum.

A Roman gesture.

A sacrifice.

A humiliation swallowed in public for the sake of the Republic.

But humiliation metastasizes in men like Nixon.

It does not dissolve.

It calcifies.

PART II — THE TRIBUNE STORY AND THE REVOLVER ON THE TABLE

In January 1963, a political grenade detonated in the Chicago Tribune.

The article alleged that in the final presidential debate of 1960, Kennedy had secretly deployed classified CIA briefings on Cuba to trap Nixon — briefings Nixon could not reveal without violating national security.

In other words:

Kennedy cheated.

Nixon’s hands were tied.

The election was rigged by secrecy itself.

Kennedy’s aides traced the leak back through phone logs, whispers, and Washington shadow-play… and found the fingerprints led straight to New York.

Straight to the 19th floor of 20 Broad Street.

Straight to Richard Nixon.

Whether Nixon leaked or not ceased to matter.

In Kennedy’s mind, the verdict was rendered:

Richard Nixon had betrayed him.

Not as a rival, but as a former vice president who had crossed the Rubicon of classified politics.

Kennedy flew to New York anyway.

But he carried the Tribune like a revolver in his pocket.

PART III — THE PRESIDENT WAITS IN THE SNOW

When the motorcade arrived at Broad Street, Kennedy refused to get out.

Secret Service agents waited.

Assistants shuffled in confusion.

Pedestrians slowed, staring through the storm at the surreal tableau forming on the curb.

Kennedy merely said:

“Tell Mr. Nixon, if he wishes to speak with the President of the United States,

he may come down.”

It was the political equivalent of forcing a former vice president to kneel.

A humiliation engineered with surgical precision.

Upstairs, Nixon saw it happen through his office window.

He understood instantly.

The president of the United States had placed him on the same level as a petitioning clerk.

For a moment Nixon considered refusing, letting the standoff bloom into scandal.

But ambition is the oxygen of certain men.

And Nixon had never blown out the ember inside him that whispered:

You will rise again.

Do not give them the excuse to declare you finished.

He put on his coat.

He entered the elevator.

He descended.

PART IV — THE CAR

The Secret Service opened the Lincoln’s rear door.

Nixon climbed inside.

Kennedy did not look at him.

Snow hissed against the windows.

And in that narrow cabin, two decades of rivalry tightened into a single confrontation.

Nixon began:

“Mr. President, I’m here as you requested.”

Kennedy turned at last —

and the temperature in the car seemed to drop another ten degrees.

What followed was not a conversation.

It was an autopsy performed on a living man.

Kennedy accused Nixon of treachery.

Nixon accused Kennedy of using privilege as a shield and a sword.

Kennedy blamed Nixon for the Bay of Pigs planning he inherited.

Nixon blamed Kennedy for exploiting secrets he didn’t fully understand.

Both men accused the other of rewriting history.

The dialogue was surgical.

Venomous.

Unfiltered in a way only possible between rivals who know each other’s deepest vulnerabilities.

Then Kennedy delivered the blow:

“No, Dick.

I won’t walk into your office.

I won’t pretend we’re colleagues.

I won’t give you that dignity.”

A dismissal, not of a meeting —

but of a man.

Kennedy tapped the seat.

The agent opened the door.

Nixon exited into the snow like a man stepping onto a scaffold.

The limousine pulled away.

And the rivalry calcified into something permanent.

PART V — THE AFTERSHOCK

Within hours the story hit the wires.

THE PRESIDENT REFUSES TO ENTER NIXON’S OFFICE.

It was an unprecedented breach of political etiquette —

the kind that makes Senate cloakrooms whisper for decades.

Kennedy’s allies applauded.

Nixon’s allies howled.

Historians blinked in confusion.

But the consequences were deeper than the headlines:

It hardened Nixon’s belief that elites conspired to humiliate him.

It intensified the paranoia that would later flower into Watergate.

It deepened Kennedy’s instinct to punish perceived betrayal.

It severed the last thread connecting the two men who had once debated labor policy in a train car during the Truman administration.

Nine months later Kennedy would be dead.

Nixon would stand at the funeral — snow replaced by November sun — and stare at the coffin of the man who had both defeated him and defined him.

The rivalry ended not with reconciliation, but with the silence of a motorcade on Elm Street.

EPILOGUE — TWO AMERICAN GHOSTS

Kennedy became myth.

Nixon became cautionary tale.

But on February 14th, 1963 —

in a snowstorm outside an office building in lower Manhattan —

they were simply two men trapped in the machinery of their own resentment.

And that moment, more than debates, more than elections, more than speeches,

revealed the truth about the Cold War generation of American leadership:

They could face down nuclear annihilation —

but not each other.

That is the hidden fault line beneath modern American politics.

A rivalry not of ideology, but of identity.

A rivalry that began in 1947…

and never found its end.

Not even in death.

News

How The Zero Fighter Destroyed Japan’s Entire Pilot Corps

August 6th, 1945. Kagoshima Airfield.The sun had barely risen over Kyushu, yet the runway already shimmered with heat. A final…

Why Eisenhower Refused To Enter Montgomery’s Field HQ – The Allied Command Insult

THE RAIN, THE COMMANDERS, AND THE WARNING THAT DIED ON THE ROAD The rain fell in hard, slanted sheets across…

Josef Mengele – The Doctor Who Became a Ghost After the World War II

THE DOCTOR WHO WALKED LIKE A SHADOW — AND THE MONSTER HISTORY REFUSED TO FORGET There are names that do…

The legendary Tuskegee Airmen, painting the skies over Europe with courage and precision, proving all the doubters wrong. But who built the nest those eagles flew from? Who forged the steel? What if I told you one of its chief architects… one of the hands that literally carved the airfield they used… was a woman they told, in writing, was “inferior for being Black”?

THE FIRST LADY OF THE RED TAILS — The Forgotten Pilot Who Built the Runways of Freedom We all know…

Why One Private Started Using “Wrong” Grenades — And Cleared 20 Japanese Bunkers in One Day

THE GRENADE THE ARMY SAID WOULD GET YOU KILLED — The Harold Moon Story May 18th, 1944. Biak Island, Dutch…

This B-17 Gunner Fell 4 Miles With No Parachute — And Kept Shooting at German Fighters

THE BOY WHO FELL FROM THE SKY — The Impossible Survival of Staff Sergeant Eugene Moran At 11:47 a.m., November…

End of content

No more pages to load