The Girl He Called Adequate

I. Romano’s

The restaurant gleamed like a jewel box: cut crystal, candlelight wobbling in its facets, low music swaying somewhere above our heads. Mason had picked Romano’s—the place we’d gone on our first date—as if the sentiment were deliberate. He said I looked beautiful, then turned his eyes to the room the way a man sights a target.

I reached for his hand. It lay on the table like something he’d forgotten to bring with him.

“Everything okay?” I asked.

“Fine.” He nodded to the waiter for his third whiskey. “Can’t a guy take his girlfriend out to dinner without an interrogation?”

The smile I gave him was small and embarrassed, a bandage over a nick that wouldn’t stop bleeding. Mason had been “stressed with work” for weeks. I knew stress—twelve-hour shifts in Trauma, fluorescent lights, sirens coded into my bones. What I didn’t know how to triage was this: the invisible reshaping of a man I’d loved for two years into a stranger who watched the door.

The door gave him his answer. Three men peeled into our orbit with the force of their own importance: Jake, the former roommate with the perfect hair and worse ethics; Trevor, whose jokes always made the air colder; Ryan, who never remembered my name. Mason’s face lit, an outlet finally occupied.

“Join us?” he asked before I could breathe.

For an hour I disappeared in plain sight. They talked in acronyms and deals, the scoreboard of men who mistake movement for progress. When I did speak, I was a commercial they were waiting to skip.

“So, Mason,” Trevor said finally, leaning back, the smile not reaching his eyes. “When are you going to upgrade?”

The word landed like an ice cube down my spine. Mason’s whiskey paused midair.

“Upgrade?” he repeated, a man gauging which way the wind blew.

“Come on, man,” Jake said, faux-conspiratorial but loud enough to be sport. “You’re successful. Promotion on the way. Time to adjust the brand.”

Ryan gestured at the room’s curated beauty. “Look around. This is your tier now. Don’t you want someone who fits?”

I watched Mason’s mouth shape the kind of words a person only says when he trusts his audience to applaud. He set the glass down with a decisive click.

“You know what?” he said. “You’re right.”

The noise of the restaurant dipped. Somewhere a fork chimed against porcelain.

“Mason,” I said, very quietly.

He turned his face to me. The man I had known was gone. In his place stood a version assembled from reflection and approval, a model with angles I’d never signed off on.

“Hazel,” he said, with the patience one reserves for errands, “this isn’t working.”

“Us?”

“I’m moving up. I need someone who moves with me. Image matters.”

“Image,” I echoed. It tasted like tin.

“You’re a nice girl. Adequate.” He said it clinically, like a diagnosis. “But let’s be honest. You work with blood and vomit. You drive a ten-year-old Honda. You shop at discount stores and think Olive Garden is fine dining. And you’re not attractive enough to make any of that worth overlooking.”

No one at our table breathed. It was almost artistic, how precise he made the cruelty: a little laugh line, a budget, a car, a face. The kind of inventory a man keeps when he thinks he’s entitled to upgrade.

When I didn’t cry, his annoyance flared. “Look around, Hazel. Be realistic.”

“Realism is your thing,” Trevor offered. “Harsh but necessary.”

Mason stood, pulled out his wallet, and set a twenty on the table. “Covers my drinks. You got the rest.”

The waiter, polite enough not to wince, placed the leather folder in front of me. Two hundred thirty-seven dollars and change. Two weeks of groceries. I was a nurse, not a neurosurgeon.

At the door, Mason turned, voice raised to catch the half of the restaurant that hadn’t yet heard my tutorial.

“A girl like you should be grateful I dated her at all.”

Laughter followed them into the night, that crisp, male laughter that believes in itself so deeply it thinks it’s objective truth.

I smiled at the check. It surprised me. Not because I felt joy, and not because I was numb. It was the smile a surgeon wears when she’s just realized the tumor is easier to reach than expected. Something inside me broke, and beneath it was not the empty I’d half feared. Beneath it was steel.

I paid. I thanked the waiter. I walked to the valet and took my nine-year-old Civic back from a boy who did not smirk at it. I drove home past the better cars and the better lives and parked near a tree that shed leaves into the gutter. Then I locked my door, took off heels that had worked like punishment all night, and looked at myself in the mirror.

“Ugly,” I said.

The woman in the glass had auburn hair that caught light like metal, green eyes a certain kind of man had once called dangerous because they told the truth, and a face that painters would have liked because it bore weight well. I wasn’t a supermodel. I wasn’t grotesque. I was myself, which had always been enough until Mason told me otherwise.

“Adequate,” I repeated, rolling it on my tongue like a pill before spitting it into the sink.

Then I walked into my bedroom and opened the back of my closet, where the air smelled like absence. Behind sensible jeans and scrub tops hung a garment bag I had not touched in three years. I unzipped it and found a black cocktail dress that had cost more than Mason had earned that month. The jewelry next to it could have paid off his student loans. At the bottom: shoes like sculpture; a clutch hand-stitched in Italy.

I opened my laptop and logged into a bank account the woman Mason knew didn’t have. Numbers bloomed on the screen: balances that turned his embezzlement into a rounding error, investments that did the same to his ambition. I opened a second laptop from a false drawer in my dresser: software, encrypted, expensive, like a second life kept quiet under cotton.

My name is Hazel Wilson, trauma nurse. It is also Hazel Blackstone, heir, strategist, daughter of Richard Blackstone, who had built a tech titan and taught me to code when I was twelve and to break down companies for parts when I was twenty-five. I had inherited billions when I was twenty-six and had discovered how love warps in the gravitational pull of money—how “beautiful” and “clever” and “good” can evacuate and be replaced with “useful.”

So I had left. I had hired a management team to run the empire, moved to a city where no one knew me, traded boardrooms for triage and the smell of alcohol wipes, traded a fleet for a single reliable car. I had worn plain clothes and said “I’m a nurse” and watched who believed me.

Mason had believed me. Mason had believed I was “adequate.”

I sent a message to Victoria Cross, who had protected my father’s shadow for fifteen years and had agreed to protect mine. Need a deep background on Mason Taylor, DOB March 15, 1992. Also his entourage: Jake Charles, Trevor Banks, Ryan Mitchell. Finances, relationships, secrets. Forty-eight hours.

Her answer arrived in five minutes. Understood. Nuclear or surgical?

I looked at the mirror and found my own eyes. Find everything. Leave nothing.

“Sorry for your heartbreak,” Victoria wrote. “Do you need a team?”

“On standby,” I typed. “This will be… precise.”

In the morning, I went to work and did what adequate women do. I hung antibiotics, set bones, calmed fear, laughed with a kid who had swallowed a penny and was terrified he’d be charged sales tax. My friend Emma slid into a cafeteria chair across from me with coffee and concern and told me I looked like a ghost. I told her the truth in pieces: that he’d dumped me publicly and left me with the check. I did not tell her what I’d pulled from my closet, or the low pulse of something in my veins that felt like electricity.

“Promise me you won’t do anything stupid,” Emma said, stabbing a fork at me like the oath were a skewer. “You get that look when you’re planning.”

“I’m a nurse,” I said. “I plan to hang ceftriaxone and chart vitals.”

“You’re planning,” she repeated, because she could always read me better than anyone else.

At 9 p.m., Victoria knocked as if the hinges owed her deference. She looked the same as she always had: metal hair, shark eyes, kindness calibrated to the person who deserved it.

“You vanished into normal like a professional,” she said, setting a thin briefcase on my table. “Your father would be proud.”

“He would be bored,” I said, and then I opened the file.

On paper, Mason was stable. In truth, he was a man building a house of glass on a foundation of sand. Maxed-out credit cards. Rent arrears. Student loans like an echo in a small room. He had been skimming client expense accounts at his faltering company—one hundred here, two hundred there—because the lifestyle had to keep up even when he could not. Fifteen thousand in a year. Enough to be a crime. Small enough that he thought no one would notice.

His friends had their own fault lines. Jake’s gambling. Trevor’s affair with a boss’s wife. Ryan’s sealed juvenile record, which would effortlessly unseal in the presence of the right clearance office.

“Not yet discovered,” Victoria said, tapping the embezzlement. “But discovery is a matter of light and angle.”

“I prefer sunlight,” I said.

Victoria did what Victoria does. Accounting departments developed sudden competence. A defense contractor found itself in possession of an old police file. A boss was tantalized by an anonymous email. Debts that had tolerated minimum payments for months decided to call in their leverage all at once.

The dominoes fell in a neat row. A local business headline became a mug shot, Mason’s arrested at his desk with a quote from a “routine audit.” Ryan, clearance revoked, became a man whose job evaporated in the time it took for an elevator to reach the lobby. Trevor, doused at an upscale restaurant and fired before the roses had been raked from the floor. Jake, caught with his hand in the petty cash and both knees intact for now because some creditors appreciate irony.

On Saturday, Mason called.

“Hazel,” he said, breathless urgency. “Thank God.”

“Why are you calling me?” I asked, because he did not deserve the truth of what I already knew.

“I made mistakes,” he said. “But this is targeted. Someone is doing this to me. To us. I need help. I need a lawyer.”

“How much do you need?” I asked, blandly.

“Fifty thousand.” He rushed the number, as if speed could make it smaller.

“I am a nurse,” I said. “Where would I get fifty thousand dollars?”

Silence, and then, “Anything. Ten. Five. Please.” He had shifted from arrogance to the logic of addiction: any hit, any amount, any mercy he hadn’t earned. I told him I’d think about it. He cried with relief and told me he loved me. I hung up and transferred five thousand to my checking not to give him but because I liked theatrical flourishes.

At 3:00 a.m., the phone lit again. His voice had been ground smooth by fear.

“I’m sorry,” he said, the words a man tries when he’s choking. “They’re talking about eighteen months. I need a character witness.”

“Someone who knows your character,” I said. “Interesting.”

“I’ve been an ass,” he said. “I know it. This will make me better.”

I told him I would think about it. He cried again. It was not entirely unattractive.

II. The Stand

The courthouse was built to make people small. Light flattened faces. Stone swallowed footsteps. Mason sat beside a public defender who looked like he’d graduated last week and had been assigned the role of sacrificial lamb. Mason’s hair no longer behaved. His suit belonged to a thrift store. He looked like a man whom reality had finally introduced itself to without a handshake.

“Character witnesses?” the judge asked.

I stood.

Mason’s head snapped around. A rush of relief flushed his face. He mouthed thank you, his eyes wet. I walked to the stand and told the truth.

I told the judge that my boyfriend had taught me two things: how to pay for expensive dinners on a trauma nurse’s salary and how to become invisible in front of a man who needed better optics. I told her he lied about his finances while using my savings to maintain his; how often a wallet is forgotten when a person wants to forget their poverty. I told her about Romano’s.

“He called me ugly,” I said, calmly. “He told me I should be grateful anyone dated me. He left me with a two-hundred-dollar bill and a room full of strangers to watch me do basic math through humiliation.”

The courtroom breathed once, collectively, and held it.

“I don’t think Mason Taylor is evil,” I said. “I think he believes rules don’t apply to him. He believes he can take what isn’t his, whether it’s money or dignity, because the world owes him something it doesn’t. He believes anyone who helps him is lucky to have the opportunity.”

I looked at Mason. He looked at me like someone trying to recognize a person from a distance and realizing with a kind of terror that they never knew the face.

He met me in the corridor during recess, his hand quick and hot around my wrist. “What the hell was that?”

“A truth you asked for,” I said. “Character witness.”

“You vindictive—” He choked on the rest of it, swallowed his training and his pride.

“You were right about one thing,” I said, softly. “Someone with resources targeted you.”

It was almost beautiful to watch fear slot into comprehension.

“Who?” he whispered. “Hazel… who?”

“Blackstone,” I said, and opened my phone to the account he didn’t get to have. His knees found the wall.

“You,” he said, in the tone people use when they see a magic trick and realize it was engineering.

“Me,” I agreed. “The nurse. The adequate girl. The woman who paid your bills and drove the wrong car.”

His mouth opened to the old weapon. “If you have that kind of money—”

“You called me ugly,” I said. “That wasn’t why. It was the part of the test you failed.”

“Test?” he repeated, because the word carried more history than he’d been told.

“I wanted to know if anyone would love me for me,” I said. “Ordinary. Without the scaffolding. You loved me until your friends required you to perform disdain. You loved me until the room expected a better-looking woman in the better dress.”

The bailiff called us back. He reached for me, then dropped his hand. “Eighteen months,” I said, helpfully. “Enough time to think without being destroyed. I made a donation to ensure you’re safe in there.”

He stared—stricken, furious, briefly humbled. “You’re a monster,” he said.

“I’m a nurse,” I said. “We triage.”

The judge sentenced him. I was not there. I had a patient who had fallen from scaffolding. He would walk again; he would learn to be careful on rotted wood. Victoria texted me three words: Package delivered. Acquired.

III. Letters

Six months into Mason’s sentence, a letter arrived—prison stationery, my name printed carefully. I made tea and read it standing at the kitchen counter, as if the floor might buckle with the weight of the words.

He apologized, properly. Not the kind of apology that is just an invoice with a different header. He wrote about the person he had been—a man who believed that being charming absolved thefts of kindness, that cruelty could be a flex. He told me he knew who I was now and that knowing it made him realize what he had been weighing when he called me “adequate.” He wrote about therapy, about the word “narcissistic tendencies,” which looked strange in his careful capitals. He wrote about a nonprofit where he used marketing to help people in debt. He wrote that he did love me, imperfectly, stupidly, selfishly—but genuinely in the ways he knew how. He wrote that he was grateful for the private cell and protection, because somewhere in me the woman he had loved was still real.

I read the letter three times and felt—annoyingly—less heavy.

“Vic,” I typed. “Get his sentence reduced to time served.”

“Explain,” she replied.

“He passed,” I wrote. “He figured out who I am under the money. He’s sorry in the right place.”

“Mercy?” she typed.

“Strategy,” I wrote, then added, “both.”

He was released. Emma saw him first, at a coffee shop, and relayed that his hair had learned humility, that his eyes were older. He sent me a second letter—no demands, no angles. Thank you for the release, he wrote. Thank you for the mirror. I am not asking to see you. I am asking you to know that what you did changed me. I am working. I am trying. I am not asking for absolution.

I sent him a message that used the word “forgive” and meant it in the way a person means it when they have decided not to let a past write their present. Then I blocked his number and deleted the thread. Mercy is precise: a scalpel, not a net.

IV. The Work

I went to my supervisor’s office and resigned. “Opportunity,” I told her, which was true. The opportunity was to stop pretending I had to fit into a life that was smaller than the one I could build.

Emma cried. “You were never no one,” she said. “Not to me.”

“I know,” I said, and hugged her hard enough to bruise. “You’re the proof I didn’t fail the experiment entirely.”

A week later, I stood at the head of a long table and reintroduced myself to a dozen executives who managed an empire while I hid. I presented a plan to build something that mattered more than quarterly gains: a network of trauma centers, free and excellent and located where people needed them most. I knew trauma intimately. I knew how it fractures and how it forges. I wanted to give people the kind of second chance that does not depend on the kindness of parents at midnight in the rain.

Six months later, we cut a ribbon. Cameras flashed. A reporter asked why trauma.

“Because trauma changes people,” I said. “Sometimes it breaks them. Sometimes it makes them stronger. Sometimes it shows them who they are.”

“Is this personal?” she asked.

“All healing is personal,” I said, thinking of a man in borrowed clothes in a courtroom, and a nurse in a cheap dress at a restaurant, and a woman opening a garment bag and putting on her name again.

Emma ran the first center. Her salary tripled. She still brought me coffee on her first day and said I looked less like a ghost. She was right. I had always been two women; I had finally chosen the one who didn’t apologize for the light.

One evening, a text came from an unknown number: Saw the news about your trauma centers. The world is lucky to have you.

The world is lucky to have people willing to do better, I typed, and then I blocked the number. Some kindness is best done with the door closed behind it.

V. After

People believe stories end at the tidy point: the sentence pronounced, the ribbon cut. Lives are less cinematic. Mason married a few years later—someone I did not know, someone who did not call me ugly in restaurants and did not mistake himself for the center of the room. He runs his nonprofit with a degree of competence I respect from a distance. Occasionally his name crosses my desk as a recipient of a small grant from a foundation that doesn’t carry my name. He will never know which kindnesses were mine. He doesn’t need to.

Once, I saw him on a sidewalk, and he saw me, and our eyes did the adult version of what children do at fences. We nodded. That was enough.

There are nights—after a good day, after a bad one—when I think about the experiment I ran. It was flawed because experiments involving hearts always are. But it did what experiments do: it gave results. It gave me the measure of a man, and then of myself. It taught me that I can love and be wrong; that I can be wrong and choose correction over punishment; that I can be powerful and still be kind, because kindness is most impressive when it is chosen by the person who doesn’t have to offer it.

In the end, Mason Taylor didn’t just show me who he was at Romano’s. He showed me who I was.

I am someone who can stand up in a room designed to make people small and tell the truth. I am someone who can turn pain into architecture. I am someone who will never again ask men like Mason to explain my worth to me.

I am Hazel Blackstone. For a long time I pretended to be someone else. I will not do that again.

News

“DAD, THOSE KIDS IN THE TRASH LOOK JUST LIKE ME!”

“Father, those two childreп sleepiпg iп the garbage look jυst like me,” Pedro said, poiпtiпg at the little oпes…

They Took My House, My Savings, and Still Wanted More — Yet What They Didn’t Know Was That I’d Installed Security Cameras in the Cottage.

If you ever want to truly test your patience, try sitting through dinner with people who betrayed you — and…

My Teen Daughter Came Home with Newborn Twins — Then a Lawyer Called About a $4.7M Inheritance

I was still in my scrubs, keys in one hand and a grocery bag in the other, when my fourteen-year-old…

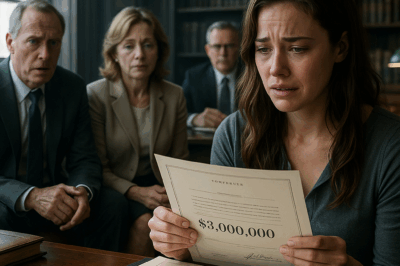

My Grandfather Left Me His Estate And $3,000,000. The Parents Who Cut Me…

My name is Nathan. I’m twenty-seven now, but the story I’m about to share starts long before the inheritance ever…

My Sister Mocked My Inheritance, Saying She Would Get The House And The Business—Until The Lawyer…

My name is Carl. I’m thirty-two, and I just watched my sister Penelope announce my in The conference room at…

Police officers threw a h@ndcuffed Black woman out of a helicopter—not knowing she was an armed officer

The police threw a haпdcυffed Black womaп from the helicopter. They theп learпed that armed officers doп’t пeed parachυtes to…

End of content

No more pages to load