When the Second World War began, the sky was not yet a battlefield after dark. Flying at night was dangerous, uncertain, and nearly blind. Pilots relied on moonlight, on stars, and often on pure instinct. Few dared to fight in the darkness because few could even find their way home once the sun went down.

But as the bombs began to fall over London and Berlin, both sides learned a terrible truth. Whoever could see in the dark would control the war above the cities.

In the late 1930s, a new kind of weapon was being born inside secret German laboratories. It was not a bomb, not a plane, but a machine that could see using invisible waves. It was called radar, radio detection and ranging. And it would change the course of the air war forever by sending pulses of radio energy into the sky and listening for the echoes. Radar could spot approaching aircraft long before the human eye could.

For the first time in history, the night sky was no longer invisible.

Germany was among the pioneers. At the Naval Research Laboratory in Keel, scientists such as Dr. Rudolfph Kunhold and Hans Holman experimented with shortwave detection systems. Their work led to the creation of the Freya radar, a powerful early warning device capable of detecting planes 100 km away. Soon came Verdzburg, a smaller but far more precise radar designed to guide anti-aircraft guns directly to their targets. These machines became the new eyes of the Reich’s air defense.

But radar alone was useless without coordination. The man who turned these machines into a weapon was General Joseph Camhuber.

After British bombers began to attack German cities at night, Kamhuber built a massive network of radar zones stretching across Western Europe. This defense belt became known as the Kamhuba line.

Each sector of this line, which the Germans poetically called Himmlbet, canopy bed, was a carefully arranged trap. A Freya radar scanned the skies for approaching aircraft. A Vertzburg radar locked onto the target with greater precision. Search light stood ready to pierce the dark and waiting nearby, engines humming, sat a night fighter, usually a twin engine messes BF-110 or a Junker’s G88, ready to intercept on command.

To the Allies, this system looked terrifying. In theory, no bomber could pass through without being detected, tracked, and destroyed.

The Luftvafa’s night fighter crews were among the most skilled in the world. They were trained to fly without seeing anything, guided only by voices from the ground and faint traces on primitive instruments. Many of them became heroes in Germany, men who hunted in total darkness and returned with victory after victory. One of them, Hineswolf Gang Schnauer, would eventually become the highest scoring night fighter race ace in history.

But there was a weakness built into this entire network. The system depended completely on ground control. Every interception had to be directed by operators watching radar screens far below. When communication failed, the pilots were blind. When radar faltered, the night swallowed everything.

While Germany built its great defensive wall of radar and search lights, Britain was learning how to break it. The Royal Air Force had already discovered that flying in close formation at night was suicidal. Instead, the RAF began sending hundreds of bombers in loose scattered streams. They relied on radio navigation, on beacons, and on Pathfinder crews to light the way.

But Britain’s real secret weapon was not in the skies. It was in laboratories. In the minds of scientists who understood that radio could deceive as well as detect, the electronic jewel between the RAF and the Luftwaffer became known as the battle of the beams.

Early in the war, Germany had used radio beams to guide its bombers precisely to their targets over Britain. The British scientist RV Jones and his team uncovered the system and began jamming the beams, turning German bombers off course and ruining their accuracy.

From that moment on, the war was no longer just a clash of armies. It had become a war of invisible signals fought in silence across the airwaves.

By 1943, the British struck back with a simple yet devastating trick. They called it window. During the night raid on Hamburg that July, British bombers released clouds of thin aluminum strips into the air. Each strip reflected radar signals, creating a storm of false echoes on German screens.

Suddenly, operators saw hundreds of phantom aircraft. They couldn’t tell which blips were real and which were fake. Anti-aircraft gunners fired into empty skies. Surge lights swept in vain. The Cam Huba line, once a precise and deadly machine, was blinded.

In the chaos, communication between radar stations broke down. Pilots received contradictory instructions, or none at all. The entire German night defense system collapsed under the weight of its own dependence on technology.

General Camhuba was furious. He demanded new radar systems, better coordination, and more flexibility. But inside the Nazi command, change came slowly. Many leaders refused to believe that their technology could be defeated by something as primitive as strips of metal.

That arrogance, that refusal to adapt, would soon cost Germany dearly.

While the Luftvafer struggled to recover its night vision, a new power was preparing to enter the fight: The United States, vast in resources, rich in industry, and ahead in radar research, was about to bring a new weapon to Europe’s dark skies.

It was an aircraft designed from the ground up for one purpose only, to hunt in darkness. Its wings were long and black, its engines powerful, and on its nose sat a glowing radar dish that could see for miles. It was the Northre P61 Black Widow, the world’s first true night fighter.

When the P-61s arrived in Europe in the summer of 1944, they began their work quietly, operating from bases in England and later in France. They patrolled the night skies, intercepting German bombers, reconnaissance planes, and even the deadly V1 flying bombs launched toward London.

Many Luftwaffer crews never saw their attackers. They were flying straight and level, thinking the sky was empty, when traces appeared out of the dark and ripped through their aircraft. For the first time, the hunters of the night had become the hunted.

But while the Americans brought superior radar and fresh energy, the Germans still had experienced pilots and good machines. They were flying the J88G and the BF-110G, both equipped with the Listenstein radar. On paper, it should have been an even match. Yet, the reality was different.

The Lichenstein radar was an engineering achievement, but it was fragile, with limited range and poor resistance to jamming. It could detect targets only within about 3 km, and its antennas created drag that slowed the aircraft down. Worse still, many German pilots didn’t fully trust it. They preferred to rely on their instincts on moonlight or on ground controllers. The idea of trusting a screen instead of their own eyes felt unnatural.

That mistrust became deadly.

American crews were trained to fight using their instruments. They practiced in total darkness, learning to trust the radar completely. Their coordination between pilot and radar operator was almost mechanical, smooth, and precise. When the radar said target ahead, the pilot didn’t hesitate. He attacked. When the radar showed a target disappearing, he broke off.

German pilots, by contrast, often ignored their radar readings. Some switched the set off to save power or avoid revealing their position. Others believed the blips were false echoes or allied decoys. In doing so, they lost the very advantage that their technology had given them.

Meanwhile, Allied engineers pushed the boundaries of electronic warfare even further. Special British units such as RAF’s number 100 group began flying dedicated electronic warfare aircraft that jammed and confused German radar. They filled the air with false signals and phantom targets, making the night skies a maze of illusions.

German radar operators struggled to tell what was real and what was trickery. And behind this curtain of noise, the Black Widows waited patiently for their prey.

The American night fighters were not only deadly, but also versatile. They hunted bombers, transports, and even lone reconnaissance planes trying to slip through the dark. Some missions were silent ambushes high above the clouds. Others were violent close-range battles that ended in seconds.

Pilots described the eerie feeling of chasing a faint radar echo through the blackness, knowing that somewhere out there was a man doing the same, but blind to their presence.

The difference between the two sides grew wider every month.

The Germans were losing radar stations to bombing raids, losing fuel, losing experienced operators. Their once coordinated night defense was breaking apart. The Kamhuba line no longer functioned as it had. Jamming, communication failures, and power shortages left entire regions uncovered. Night fighters scrambled with little guidance, hoping to find targets by chance.

The Americans, on the other hand, grew stronger. By late 1944, more P-61 squadrons were active across Europe. Their crews operated with confidence and precision. In some missions, they guided British bombers through radar storms. In others they hunted German intruders attempting to attack Allied airfields.

Every night, the balance shifted a little more.

The Luftbuffer still had its heroes. Hines Wulfgang Schnauer for example continued to score victories even as the war turned against Germany. He was a master of the old system using a mix of radar guidance and instinct to find his targets. But even he could not change the outcome. The technological tide was against him.

By early 1945, the once-feared German night defense was collapsing. Many radars were destroyed or out of service. Replacement parts were scarce. The crews were exhausted, the planes worn out, and the pilots inexperienced. Every night, Allied bombers came in waves, their paths protected by radar, their escorts hidden in the dark.

The German night fighters that once struck terror now flew blind. Outnumbered and outmatched. And above them, silent and unseen, the black widows prowled.

The air war over Europe had entered a new phase, one no longer ruled by courage alone, but by the invisible power of science.

By the spring of 1945, Germany’s air defense was a shadow of its former strength. The cities that once glowed with search lights were dark and silent now, their power plants destroyed, their radar stations abandoned. The mighty Kamhuba line, once the pride of the Luftwuffer, was in ruins, the Freya and Verzburg radars that had guarded the Reich for years now stood shattered in empty fields.

Communication cables were cut, command centers bombed, and skilled radar operators were either killed or captured. The air defense system that had once been the most advanced in Europe had collapsed under the relentless pressure of Allied bombing and electronic warfare.

Everywhere the night skies belonged to the Allies.

British bombers roared across Germany in massive formations, guided by radar, radio navigation, and pathfinder flares. American night fighters, the Black Widows, flew quietly above them, scanning the dark for any sign of movement. If a German aircraft appeared, it rarely lasted more than a minute.

The Luftvafer’s once proud night fighter units were now outnumbered, underequipped, and exhausted. Pilots took off knowing that their chances of returning were slim. Many flew without ground control or radar support, relying only on instinct and luck. For the first time since the early days of the war, German pilots truly understood what it meant to fight blind.

Those who survived told haunting stories. They described endless nights of confusion, radar screens filled with noise, false alarms, and phantom signals. They spoke of trying to intercept bombers that no longer flew where they were expected to be. They spoke of silence on the radio, of commands that never came, of entire squadrons that vanished into the darkness.

Even the best of them, like Hines Wolf Gang Schnauer, could feel the end coming. Schnafa continued to claim victories until the final months, but he was now an exception in a system that was falling apart. His aircraft was one of the few still fully equipped and maintained. Around him, his comrades were flying outdated planes with broken radar sets and little fuel.

The Germans tried to innovate until the very end. New radars were tested, such as the Fugi 220 Likenstein SN2 with improved range, but they came too late. Allied jamming made many of them useless. The British and Americans had learned how to flood the airwaves with interference, drowning out enemy signals. The Luftwaffer’s night fighters were flying through a storm of invisible noise.

As the allies advanced across Europe, they captured many of these radar sites and studied the technology. They were surprised by how advanced some of it was. The German engineers had built extraordinary devices, sensitive, powerful, years ahead of their time. But all of it had failed for one reason. It depended on perfect coordination between men and machines. And by 1945, the men were gone. The machines were broken, and the command structure no longer existed.

The collapse of the Luftvafer’s night defense was not just a military failure. It was a lesson. It showed that even the best technology means nothing without adaptability, training, and trust. The Germans had developed radar first, but they had not learned how to use it to its full potential. Too many pilots ignored their instruments. Too many commanders refused to change tactics. And by the time they realized it, it was too late.

The Americans, meanwhile, had embraced the new way of war. They built systems that worked even in chaos. Radar that could be used independently by pilots, networks that could adapt when communication failed. Their philosophy was simple. Train men to trust their instruments, and the instruments will keep them alive.

When the war ended in May 1945, the skies over Europe were silent again. The Great Bombers no longer roared across the night. The Black Widows returned to their bases, their radar screens dark for the first time in months. The men who flew them knew they had seen something new, a kind of warfare that would shape the world to come.

Because radar was not just a weapon, it was the beginning of a revolution.

In the years that followed, scientists from all sides, British, American, and even German, worked together to build new generations of radar systems. They designed better antennas, faster to computers, and eventually the great airborne warning systems that would protect the skies during the Cold War.

The lessons learned in those black knights over Europe became the foundation of modern air defense. But the technology that once guided the P-61s, guns would one day guide missiles, track satellites, and control entire air fleets. The invisible waves that once revealed bombers over Hamburg and Berlin would one day detect space debris orbiting Earth.

And yet, behind all the progress, the human story remained the same.

During the war, countless young men on both sides learned to fight without sight, to trust the hum of a radar set, the voice of a crewman, the rhythm of a machine. Some ignored those signals and died. Gathers listened and survived.

In that sense, the phrase German pilots ignored radar was more than just a description of tactics. It was a warning, a reminder that pride and habit can destroy even the most advanced system. The Americans did not win the night because they had better machines. They won because they trusted them.

Radar had changed the nature of war. No longer did victory depend only on eyesight or courage. It depended on understanding, adaptation, and the ability to think beyond what the human senses could perceive.

In the dark skies of Europe, a new kind of soldier was born. One who fought not with sight, but with signals.

When the lights came back on in 1945, the world could finally see what had happened. The cities were gone, the skies were quiet, and the age of electronic warfare had begun. The race to master the invisible had decided the fate of nations.

And as the wrecks of the Luftvafer’s night fighters lay scattered across Europe, the last generation of Black Widow crews flew home, carrying with them the lessons of the unseen war, the war that had been fought not by daylight, but by radar, by discipline, and by faith in a machine that could see what men could not.

When the guns finally fell silent in 1945, the world began to count the cost of the greatest war in human history. Cities lay in ruins. Millions were dead. But in the quiet that followed, another reckoning began. One not fought with weapons, but with knowledge.

For six long years, scientists and soldiers had worked together to push technology to its limits. Out of fear and destruction, they had created something new, the ability to see the unseen.

Radar had not only helped win the war, it had changed how humanity would think about the sky, about distance, and about safety.

After Germany’s surrender, Allied engineers rushed to capture what remained of the Luftvafer’s radar network. In empty fields and bombed out bunkers, they found machines that looked strange but familiar. Freya Fzborg Likenstein Knox. Many of them were damaged, but their design fascinated the Americans and the British. In some ways, German radar technology had been ahead of its time.

News

ch1 December 11, 1941 – When Germany Declared War on America

December 11th, 1941. Berlin.A gray morning over the Reich capital. The air is sharp, heavy with winter, and heavier still…

After Our Divorce My Ex Married His Mistress! But A Guest Said Something That Made Him Turn Pale..

After the final, suffocating dinner with my ex-husband, I made the decision to pack up my entire existence and move…

I left the country after our divorce, ready to close that chapter forever. But on the day of his extravagant wedding, everything collapsed — and suddenly his bride was calling me, her voice trembling as she begged me to listen

I got divorced and moved to another country to start fresh. Soon after, my ex-husband married the woman he’d been…

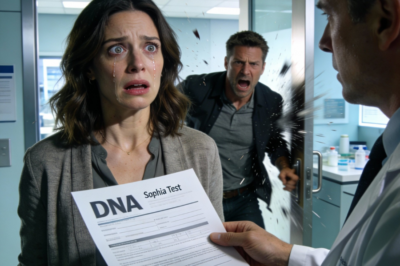

My Husband Demanded A DNA Test For Our Daughter — What The Results Revealed Shattered Everything…

Sophia Miller had always believed her life was built on solid ground—a stable marriage, a thriving career, and her bright-eyed…

My husband files for divorce, and my 10-year old daughter asks the judge: “May I show you something that Mom doesn’t know about, Your Honor?” The judge nodded. When the video started, the entire courtroom froze in silence.

When my husband, Michael, unexpectedly filed for divorce, the world beneath my feet seemed to crack open. We had been married…

A Bully Called Police to Handcuff a New Girl — Not Knowing She Was the Judge’s Daughter

«She stole it! Somebody call the cops!» Griffin Hale’s voice explodes across the library. Thirty heads snap toward the back…

End of content

No more pages to load