June 4th, 1943. Railroad Street, Mexia, Texas. The pencil trembled slightly as Unafitzia Verer Burkhart wrote in his hidden diary, recording words that would have earned him solitary confinement if discovered by his own officers. The Americans must be lying to us. No nation could possess such abundance while fighting a war on two fronts.

Through the train window, he had just witnessed something that contradicted three years of Nazi propaganda. Electric lights blazed from every farmhouse, every street corner, every shop window. An endless constellation of electricity stretching across the Texas plains at 10:00 at night.

In Germany, blackout regulations had plunged the Reich into darkness since 1940. Even before the war, rural electrification reached barely 20% of German farms. Yet here, in what Nazi propaganda had described as a decadent collapsed America, electricity flowed like water.

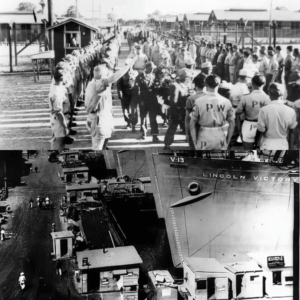

1,850 veterans of Irwin RML’s Africa Corps stepped down from the passenger train. Not cattle cars, not freight wagons, but cushioned Pullman coaches with dining services and sleeping bs. The entire population of Mexia had turned out to witness their arrival.

What none of them knew was that this moment would trigger the most profound psychological transformation in modern P history, a systematic demolition of Nazi ideology through the sheer display of American industrial capacity. The mathematics of Allied victory were being written not in battle plans, but in production statistics that would soon shatter every assumption these soldiers carried about their enemies, their homeland, and their cause.

The collapse had begun on May 13th, 1943 in Tunisia. General Jurgen Fonarnim, Raml’s replacement, surrendered along with approximately 250,000 to 275,000 German and Italian soldiers. The numbers varied as scattered units continued surrendering over several days. The Vermacht’s most experienced desert fighters, men who had driven the British back to Egypt, who had earned the grudging respect of Montgomery himself, were suddenly prisoners.

Among them was Hedman Friedrich Radka, holder of the Iron Cross first class, veteran of the France campaign, wounded twice in North Africa. His diary, discovered decades later in the National Archives, would provide historians with the most detailed account of the psychological impact of American captivity on German soldiers.

The journey from defeat to revelation began in the port of Oruran, Algeria. As Radkkey and 30,000 other PS waited in makeshift camps for transport ships, American efficiency was already beginning to crack their preconceptions. The US Army processed thousands of prisoners daily with an organizational precision that exceeded anything the Vermacht had achieved even at the height of its power.

Identity cards photographed and filed. Medical examinations completed, inoculations administered, Geneva Convention rights explained in fluent German by American officers who had been trained specifically for this moment.

But the first real shock came with the food. Oberrighter Hans Müer, captured with the 21st Pancer Division, wrote to his mother 8 months later.

In the cage at Oruran, while we waited for ships, the Americans fed us better than we had eaten in six months of desert warfare. White bread, real coffee, meat twice a day. We thought it was propaganda, that they were trying to impress us. We didn’t realize this was their standard military ration.

The Liberty ships that would carry them across the Atlantic were themselves monuments to American industrial capacity. The SS Robert E. Piri had been built in 4 days, 15 hours, and 29 minutes at Kaiser shipyards in Richmond, California. A fact that would have been dismissed as impossible propaganda if the Germans had known it.

These vessels, produced at a rate of three per day at the peak of production, were returning from delivering supplies to the European theater. Rather than sail back empty, they carried human cargo up to 30,000 PSWs per month by summer 1943.

The two-week Atlantic crossing in July 1943 provided the second phase of psychological demolition. Feld Kurt Zimmerman of the 90th Light Division kept a detailed account that survived in letters to his family after repatriation. The ship’s crew, he noted, disposed of more food waste each day than his entire company had received in weekly rations during the final months in Africa.

The American sailors threw away halfeaten steaks, whole loaves of bread, gallons of milk that had sat too long, Zimmerman wrote. They did this openly, without thought, not to mock us, but because to them this waste meant nothing. Their supply was limitless.

The ships themselves became floating classrooms in American power. Ps discovered that the vessel carrying them was one of 2,710 Liberty ships that would be built during the war. Each one requiring 250,000 parts assembled from components manufactured in 32 states.

The engines, they learned from talkative American guards, were built in three separate factories, each producing 900 horsepower cylinders that were then assembled in ports that had barely existed 2 years earlier.

Latutenant Colonel Wilhelm von Stoburn, whose aristocratic Prussian family had served in every German war since Frederick the Great, would later write in his memoirs, “As our ship approached the American coast, I watched the radar antenna rotating above the bridge. This technology, which we believed only we, and perhaps the British possessed in limited quantities, was standard equipment on a cargo vessel.”

It was then I first suspected that Germany had already lost the war.

August 2nd, 1943, Norfolk Naval Base, Virginia. The first sight of America shattered the last remnants of Nazi propaganda about American industrial weakness. The Norfolk base sprawled across 4,300 acres, its docks stretching for miles, its cranes loading and unloading dozens of ships simultaneously. In a single day, this one port handled more tonnage than the entire German port of Hamburg managed in a week.

Gerright Yoan Vber, a factory worker from the ruer before his conscription, counted 47 cargo ships in various stages of loading or unloading. Each crane, he noted in his secret diary, lifted loads that would have required a dozen men and horses in Germany. They moved with electric power, smoothly, continuously, without the coal smoke that choked our industrial cities.

The prisoners were formed into columns for the march to the waiting trains. Along the route, they passed parking lots filled with civilian automobiles, hundreds of them belonging to dock workers. In Germany, private automobile ownership remained a privilege of the wealthy and the party elite. The Volkswagen, promised to the German people since 1934, remained a propaganda dream with fewer than 1,000 ever delivered to civilians.

Here, ordinary laborers drove to work in their own cars.

But nothing prepared them for the trains themselves.

Not box cars, not the 40 and 8 wagons, 40 men or eight horses that had carried German troops across Europe, but full passenger coaches. Pullman cars with padded seats that converted to sleeping berths. Dining cars with white tablecloths and silver cutlery. Observation cars with panoramic windows.

Hedman Radka wrote, “We boarded like tourists, not prisoners.”

The American guards seemed almost embarrassed by the comfort. One sergeant apologized that the air conditioning wasn’t working properly in our car. Air conditioning. In August, we had believed such luxury existed only in Hitler’s personal train.

The 3-day train journey from Norfolk to the camps of Texas and Oklahoma would prove more destructive to Nazi ideology than any military defeat. As the trains rolled through Virginia, the prisoners pressed their faces against windows, witnessing an America that couldn’t exist according to everything they had been told.

Every small town blazed with illumination. Martinsville, Danville, Greensboro, communities that in Germany would have been lucky to have a single electric street lamp displayed illuminated shop windows, electric signs, houses with lights burning in multiple rooms.

The trains passed factories running night shifts, their windows glowing, parking lots full even at midnight.

Oberg writer Merr, whose father was a Nazi party block leader in Hamburg, wrote in a letter discovered in 1987. We passed through dozens of cities that first night. Everyone had more electricity than all of Hamburg. The guards told us this was normal, that every American town had electricity since the 192s. I called him a liar. He just shrugged and said we would see.

In Rowan Oak, Virginia, the train stopped for water and coal. The prisoners watched as American railway workers performed in 30 minutes what would have taken 2 hours in Germany. Automated coal loaders, electric water pumps, mechanized lubrication systems. Every aspect of the operation demonstrated technological superiority.

More disturbing still was the casual wealth of the workers themselves. They wore leather boots that would have cost a German laborer two months wages. They drank Coca-Cola from glass bottles and threw the empties into bins without thought. They smoked cigarettes continuously, stubbing them out half finished.

Feld vable Hinrich Müller, an electrical engineer from Seammens before the war, calculated that the single railway yard they stopped in used more electricity in 1 hour than his entire district in Berlin used in a day.

“The waste was magnificent,” he wrote. “They left lights burning in empty buildings. Electric fans ran in vacant rooms. It was the carelessness of infinite resource.”

As the trains crossed into Tennessee and Kentucky, the prisoners encountered American industrial power in full display. Through the windows, they watched endless factories, each one larger than anything most had seen in Germany.

The Alcoa aluminum plant in Tennessee stretched for 3 m along the river, its electric furnaces consuming 175,000 kW of power, more than the entire city of Munich.

Near Louisville, the trains slowed as they passed the Rubbertown complex, where synthetic rubber plants had sprung from empty fields in just 18 months. Four massive facilities, each employing thousands of workers, producing 800,000 tons of synthetic rubber annually.

Germany, despite inventing the process, had never managed more than 120,000 tons in its best year.

Oberloitant Eric Hoffman, a chemist from IG Farbin, understood the implications immediately. In a post-war interview, he recalled, “I knew those plants. I could see the distillation columns, the catalytic crackers. Each facility was more advanced than anything we had built, and there were four of them just in this one location.”

“They told us there were dozens more across the country.”

The trains passed Ford’s Willow Run plant outside Detroit, visible from miles away. This single factory, built in just 9 months, produced a B-24 Liberator bomber every 63 minutes.

At peak production, 42,000 workers assembled bombers from 1,550,000 parts manufactured by 1,500 subcontractors. The plant consumed 2.5 million square ft of floor space and used more electricity than the entire German city of Cologne.

Hutman Verly, a Luftvafer pilot shot down over Tunisia, pressed his face against the window as they passed. He counted 17 B-24s in various stages of completion visible from the train.

“We had been told American planes were inferior, hastily built, would fall apart in combat, but I could see the precision of the assembly lines, the quality of the construction. These were not inferior aircraft. They were simply built faster than we could imagine possible.”

The deeper the trains penetrated into America, the more complete became the destruction of Nazi mythology. In St. Louis, they crossed the Mississippi River on the Eids Bridge, while below them, barges carried more grain than the entire German harvest of 1942.

The prisoners could see grain elevators stretching along both banks, each one holding enough wheat to feed a German city for months.

Unraicia Carl Schmidt, a farmer’s son from Bavaria, wrote in his diary, “The Americans transport food as we transport ammunition in endless quantities without concern for loss. I watched them loading a single barge with enough wheat to feed my entire village for 5 years. The crane operator was eating a sandwich with meat thicker than our weekly ration.”

In Kansas City, the train stopped at a massive stockyard where tens of thousands of cattle waited for slaughter. The smell of meatacking plants filled the air for miles.

German PS who had subsisted on 200 g of meat per week in Africa when lucky watched American workers eating beef sandwiches during their lunch break. They ate meat like we ate bread, wrote griefer Paul Fischer. “No, that’s wrong. They ate meat like we wished we could eat bread.”

“The guard bought us hamburgers from a stand near the station. Meat, cheese, vegetables on white bread for 15. He bought 20 of them without thinking, paid with a single dollar bill. This was not special. This was their normal food.”

The arrival at the camps themselves provided the next level of cognitive demolition.

Camp Hearn, Texas, built in just 4 months, housed between 3,000 and 4,800 prisoners in conditions that exceeded what most had known as civilians. Wooden barracks with electric lights, flush toilets, hot showers, and steam heat. Each building constructed with more lumber than entire German villages possessed.

The camp hospital astounded the medical personnel among the prisoners. Oberst, Lieutenant Colonel Dr. Friedrich Bower, chief surgeon of the 164th Light Division, found himself in a facility better equipped than most German civilian hospitals.

X-ray machines, surgical equipment, pharmaceutical supplies that had been unavailable in Germany since 1941. All standard provision for enemy prisoners.

“They had penicellin,” Dr. Bower would later testify, “this miracle drug that we had only heard rumors about. They used it freely, even on prisoners with minor infections. German soldiers were dying for want of basic sulfur drugs, and the Americans were giving us their most advanced medicine without hesitation.”

The camp kitchen became another classroom in American prosperity.

Prisoners assigned to cooking duties discovered walk-in refrigerators, electric mixers, automated dishwashers, and gas ranges that could prepare meals for 5,000 men.

The daily ration included fresh milk, eggs, meat, vegetables, and white bread, quantities that German civilians hadn’t seen since 1939.

Feldwable Otto Krebs, a former hotel chef from Munich, wrote, “Today, we threw away more food than my family has seen in 3 years. Not spoiled food, simply excess. The American regulations require we prepare 10% more than needed to ensure every prisoner receives full rations. The surplus is discarded. I wept as I threw perfectly good bread into the garbage.”

By September 1943, the labor shortage in American agriculture led to the employment of PWs in fields and factories across the country. This decision, driven by necessity, would prove more destructive to Nazi ideology than any propaganda program could have achieved.

Groups of prisoners were trucked daily to work sites, traveling through the American heartland without blindfolds or restricted routes. They saw everything. The endless fields of corn and wheat, the factories running three shifts, the shops full of goods, the parking lots full of cars, the houses with refrigerators and radios.

At a cotton gin outside Houston, Unraitzia Herbert Lang watched a single machine process more cotton in 1 hour than his entire village could have handled in a month using traditional methods. The jin was powered by electricity from the Colorado River Authority, part of a rural electrification program that had brought power to 90% of Texas farms by 1943.

The farmer who owned the jin was nobody special, Lang recorded. Not aristocracy, not a party member, just a farmer. Yet he had electricity, running water, a truck, a car, and a tractor. His workers, including the Negroes, ate lunch from boxes containing more food than German workers received in a week. And this was normal. Every farm we passed was the same.

In Nebraska, prisoners worked in sugarbeat fields, witnessing agricultural mechanization that defied comprehension. A single combine harvester, they learned, could do the work of 100 men. The fields stretched to the horizon, each one larger than entire German counties.

The farmers spoke casually of yields that would have been fantasy in Germany, 60 bushels of wheat per acre compared to Germany’s 30 on the best land. Gefrighter Wilhelm Hoffman working on a farm outside Scotsluff wrote, “The farmer’s son, a boy of 16, drove a tractor worth more than everything my father had earned in his lifetime. When I mentioned this, the boy laughed and said it wasn’t even a particularly good tractor. His father was waiting for a new model from John Deere that would be even better.”

The most devastating revelations came to those prisoners who worked near or in American factories. While Geneva Convention rules prohibited direct war production work, PSWs could work in industries that freed American workers for military production. This technicality allowed thousands of German prisoners to witness American industrial capacity firsthand.

At a Campbell soup factory in New Jersey, prisoners watched production lines that processed more tomatoes in a single day than most German factories handled in a month. The facility operated with a skeleton crew of women and elderly men as most young workers were in the military. Yet production exceeded peacetime levels.

Stabsfeld Webel Ernst Vagnner who had worked in a German food processing plant before the war documented the experience. Everything was automated. Electric conveyor belts, automatic filling machines, steam cookers that processed hundreds of cans simultaneously. One elderly woman monitored controls that managed what would have required 50 workers in Germany. She did this while listening to a radio and drinking coffee.

Near Detroit, prisoners unloading coal at a power plant gained glimpses of the automotive industry’s conversion to war production. The River Rouge complex, visible across the water, employed 100,000 workers producing jeeps, aircraft engines, and tanks. The plant consumed 1.5 million kows of electricity daily, more than the entire city of Hamburg.

“We could see the parking lots,” wrote Oberrighter France Kelner. “Thousands of cars belonging to workers. Workers in Germany. Even our officers rarely owned cars. Here, factory workers drove to work. The guard told us many workers owned two cars, one for work, one for family use. We thought he was mocking us.”

By winter 1943, the cumulative impact of these observations was producing what American intelligence officers called ideological collapse syndrome among the prisoners. The special projects division, the secret re-education program run by the prost marshall general’s office documented increasing numbers of prisoners requesting access to American newspapers, books, and educational materials.

Major Paul Noeland, a member of the monitoring team, reported in December 1943. “The prisoners no longer argue when shown production statistics. They have seen too much. The most fanatical Nazis have become quiet. They still maintain loyalty to Germany, but no longer speak of victory. Many openly question what they were told about America.”

The camp newspapers produced by prisoners themselves began reflecting this transformation. Dear roof, the call published at Fort Kierney, Rhode Island, gradually shifted from defiant nationalism to discussions of democracy, economic systems, and postwar reconstruction. The editors, carefully selected anti-Nazi prisoners, found their audience increasingly receptive.

Litnant Herman Guts, captured with the 10th Panza Division, wrote in a letter that passed American sensors. “We were told America was a mongrel nation, weak, divided, controlled by Jews, incapable of military prowess. Every day I am here, I see the opposite. This is the most organized, unified, and powerful nation on earth. We were told fairy tales by criminals.”

The most devastating blow to Nazi ideology came from an unexpected source. The treatment of Italian prisoners after Italy’s surrender in September 1943. Italian PS who agreed to cooperate were formed into Italian service units given better quarters, increased pay, and more freedom. German prisoners watched their former allies working alongside Americans, eating in American restaurants, some even dating American women.

Hedman Friedrich Schulz wrote, “The Italians betrayed us, yet they are treated better than we treated them as allies. They work freely, earn money, send packages home. The Americans show them no hatred. This democracy we were taught to despise appears more honorable than our own system.”

Christmas 1943 provided the most profound psychological impact. American organizations, churches, and civic groups sent 500,000 Christmas packages to German PS, enemies who had been trying to kill American soldiers months earlier.

Each package contained cigarettes, candy, toiletries, and games. Local communities invited prisoners to Christmas dinners, though regulations prevented most from accepting. At Camp Hearn, Texas, the local Methodist church choir performed Christmas carols in German for the prisoners. Women from Hearn sent in homemade cookies and cakes. The Boy Scouts delivered handmade Christmas cards.

This kindness toward enemies shattered the final remnants of Nazi racial theory.

Oberloitant Walter Mueller, whose brother had died in the bombing of Hamburg, wrote, “They know we are their enemies. Many have sons and husbands fighting against our armies. Yet they show us Christian charity, not propaganda, but genuine kindness. What kind of people treat enemies this way? Only those absolutely certain of victory and secure in their power.”

The Christmas feast itself defied comprehension. turkey, ham, mashed potatoes, gravy, vegetables, pies, ice cream. Quantities of food that Germany hadn’t seen since before the First World War. The prisoners ate until they were sick, unable to comprehend such resources being lavished on enemies.

“We ate like kings,” wrote Feld Veeble Hansa. “Better than German generals eat, better than party leaders. And this was not special. The guards told us this was a normal American Christmas dinner, that every American family was eating the same meal. If they can feed prisoners this way, what must their own soldiers eat?”

By early 1944, over 40,000 German prisoners were enrolled in educational programs. They studied English, American history, mathematics, and sciences. The University of Chicago provided correspondence courses. Stanford University sent professors to lecture on democracy and economics.

The thirst for knowledge was insatiable. Prisoners who had been told Americans were culturous barbarians discovered libraries with millions of books, universities that welcomed all social classes, scientific research that led the world. They read American newspapers freely, comparing multiple viewpoints, something impossible in Nazi Germany.

Hman Dr. Wilhelm Fon Brown, a physicist conscripted from the Kaiser Vilhelm Institute, attended lectures on atomic physics at Camp Shelby. He later wrote, “American professors, including Jewish refugees from Germany, taught us without hatred. They spoke of science as universal, belonging to all humanity. They were years ahead of German research, and they shared knowledge with enemies. This generosity of spirit was incomprehensible to minds shaped by Nazi ideology.”

The camp theaters showed American films, not propaganda, but regular Hollywood productions. Prisoners watched Gone with the Wind, seeing a depiction of American defeat and recovery that resonated with their own situation. They saw The Grapes of Wrath, amazed that Americans would show such self-criticism to enemies.

“They hide nothing,” wrote litnant Joseph Kramer. “They show their problems, their failures, their conflicts. Yet this honesty makes them stronger, not weaker. In Germany, such criticism would mean death. Here it is considered patriotic.”

Spring 1944 brought expanded prisoner labor programs as American production reached its peak. German PSWs worked in caneries, mills, and fabrication plants, witnessing the full might of American industrial capacity. The numbers told a story that no propaganda could counter.

At the Higgins Boat Factory in New Orleans, prisoners unloaded steel that would become landing craft for D-Day. They watched as workers assembled 700 boats per month, each one requiring 20,000 parts. The factory employed 20,000 workers, including thousands of women who operated cranes, welded hulls, and managed production lines.

Stabsfeld Weeble Curt Zimmerman wrote, “Women doing men’s work, Negroes operating complex machinery, teenagers running drilling equipment, everything we were told was impossible in a democracy. Yet production never stopped. Three shifts, 24 hours, 7 days a week. They produced more boats in a month than our entire Navy built in a year.”

At Republic Steel in Ohio, prisoners witnessed the production of 10,000 tons of steel daily. The blast furnaces ran continuously, fed by endless trains of iron ore from Minnesota and coal from Pennsylvania. The scale defied German comprehension.

“This single plant produced more steel than the entire rur at its peak. I worked at Crook before the war,” wrote Oberw writer Paul Hartman. “I thought I understood industrial production, but this was beyond imagination. They wasted more steel in spillage than we could produce. The workers complained about overtime while producing quantities we couldn’t achieve with slave labor and double shifts.”

The summer 1944 harvest provided the final demolition of Nazi propaganda about American weakness. German prisoners worked across the Midwest, witnessing agricultural production that could feed the world.

In Kansas, they watched wheat harvests where single farms produced more grain than entire German provinces. Combines moved across fields like ships across an ocean of gold, each one harvesting 100 acres per day. The grain elevators they filled could hold more wheat than Germany imported in an entire year.

Untafitzia France Vber, a farmer from East Prussia, wrote, “One American farmer with machinery does the work of 100 German farmers. They showed me aerial photographs of the wheat fields — thousands of square miles of grain. They could lose half their harvest and still have more than all of Europe combined.”

In California’s Central Valley, prisoners picked fruit in orchards that stretched beyond the horizon. They watched as perfectly good fruit was discarded for minor blemishes, fruit that would have been treasured in Germany. Entire crops were sometimes plowed under to maintain prices, a concept that caused psychological breakdown among prisoners from hunger-ravaged Germany.

“They destroyed food to keep prices stable,” wrote Gerriter Otto Schultz. “Mountains of oranges bulldozed into pits because they had too many. We begged to be allowed to send them to Germany to our families. The guards were sympathetic but explained it was impossible. The waste was strategic — proof of unlimited resources.”

News

“He Left Me for Another Woman. How Do I Move On?”

About a year ago, I met a man – “Ryan” – who was on a work assignment in my town…

The restaurant manager knocked my water over and cleared my table for a famous actress. “This table is for celebrities, not for nobodies in t-shirts. Get out.” I texted the Board. Immediately, the head chef turned off the stoves and walked out with the entire staff. He bowed to me: “Boss, we are quitting as ordered. No one is cooking for that actress.”

L’Orangerie was never merely a restaurant. In the fevered imagination of Los Angeles, it was a cathedral, a sanctuary where the…

ch1 Japan Built an “Invincible” Fortress. The US Just Ignored It

In 1944, the Japanese Empire had a plan to win the war. It was simple, brutal, and based on centuries…

ch1 How One Sonar Operator’s “Useless” Tea Cup Trick Detected 11 U-Boats Others Missed — Saved 4 Convoys

March 1943, the North Atlantic.A British corvette pitches violently through 20ft swells. Spray crashing over her bow every few seconds….

ch1 The Germans mocked the Americans trapped in Bastogne, then General Patton said, Play the Ball

The other Allied commanders thought he was either lying or had lost his mind. The Germans were laughing, too. Hitler’s…

‘There wasn’t enough room in the car, so leave her at home.’ My 6-year-old daughter left the lights on all night while they took my sister’s kids on a yacht; I didn’t cry, I pressed one button… and overnight, the family mask fell off…

My parents left my six‑year‑old daughter alone in their house for a week and went on a luxury vacation with…

End of content

No more pages to load