THE NIGHT USS BARB SENT WAR TO JAPAN’S SHORES

At 11:58 p.m. on July 23rd, 1945, Commander Eugene “Lucky” Fluckey stood in the conning tower of USS Barb, 950 yards off the coast of Karafuto. He watched eight sailors paddle toward Japanese territory in two rubber boats.

Eight men.

Unmarried.

Hand-picked.

And carrying a 55-pound bomb wired to a homemade micro-switch inside a pickle jar.

They were rowing straight toward the Japanese homeland.

No American combat troops had ever landed on Japan’s home islands.

These eight would be the first.

FLUCKEY AND THE BARB — A LEGEND BEFORE THE MISSION EVEN BEGAN

Fluckey was 31.

Five wartime patrols.

Seventeen ships sunk.

The only submarine skipper to fire rockets at shore targets.

During the Barb’s 45-day patrol, the crew:

Launched the first submarine-fired rockets in naval history

Bombarded coastal targets with deck guns

Sank cargo ships and patrol craft

But shipping targets had vanished by summer 1945.

Japan’s merchant fleet was ruined.

Convoys stayed in port.

The Navy needed new ways to hurt Japan.

Then came the idea—hit the railways.

The coastal line was booming with traffic.

In the last month alone, 400 trains had run along the very track the Barb now stared at—full of ammunition and troops moving south to repel a coming American invasion.

Destroy a train?

Useful.

Destroy the tracks?

Devastating.

The idea belonged to Chief of the Boat Paul “Swish” Saunders.

The target: a railway less than 2,000 feet from the beach.

Fluckey called for volunteers.

Every man aboard raised his hand.

He chose eight.

Requirements:

Unmarried. Former Boy Scouts.

Navigation and discipline were key.

If things went wrong, Fluckey had given them orders:

“Head north to Siberia. Survive as long as you can.”

But Fluckey had no intention of losing a single sailor.

Not on his command.

THE LANDING PARTY

12:07 a.m. — Touchdown on Japanese Soil

Lieutenant William Walker was first to step onto Japanese sand.

Behind him, seven sailors hauled the two rubber boats up the beach.

The beach gave way to pine trees, then a drainage ditch, then a coastal road.

Beyond that, 1,500 feet of open ground leading to the tracks.

Time to dawn: ~90 minutes.

Walker split the party:

Team 1 crossed the open ground first to secure the site.

Team 2 held back with Hatfield and the bomb.

No patrols.

No civilian traffic.

No barking dogs.

It felt unreal.

But dawn was coming.

THE BOMB

Enter Electrician’s Mate Third Class Billy Hatfield.

As a boy, Hatfield placed walnuts on tracks and watched trains crack them open.

Now, that childhood memory became Navy sabotage tech.

Inside a pickle jar:

a micro-switch

three batteries

wiring to a 55-pound scuttling charge

When a train rolled over the switch, the downward flex of steel rails would close the circuit.

Simple physics. Catastrophic results.

Hatfield dug between the ties.

Lowered the bomb.

Lined the switch beneath the rail.

Buried everything beneath gravel.

Time: 12:41 a.m.

The device was armed.

Now they needed a train.

EVACUATION UNDER THE CLOCK

12:47 a.m. — Departing the Tracks

They erased their footprints, brushed gravel smooth, hid all evidence.

They crossed the 1,500 feet back—more slowly this time, adrenaline drained.

The first signs of dawn were faint gray streaks.

1:05 a.m. — Launching the Boats

They reached the surf.

Shoved off.

Paddled hard.

1:18 a.m. — Aboard USS Barb Again

Fluckey greeted them with a simple check of his watch.

71 minutes ashore.

Zero casualties.

Mission status: pending.

THE WAIT

1:30 a.m.

No explosion.

2:00 a.m.

Still nothing.

2:25 a.m.

Dawn approaching. Hope fading.

Then—

2:32 a.m. — SONAR CONTACT

A surface contact moving landward at 30 mph.

A train.

Fluckey returned to the periscope.

2:37 a.m. — 4 miles

2:40 a.m. — 3 miles

2:42 a.m. — 2 miles

2:45 a.m. — 1 mile

No slowing.

No suspicion.

A fully loaded Japanese locomotive was barreling straight toward Hatfield’s device.

2:47 a.m. — THE EXPLOSION

The horizon flashed white.

A column of flame erupted 200 feet into the sky.

The locomotive’s boiler detonated.

It vaporized.

Cars behind it crushed forward:

Car 1: accordion-folded

Car 2: climbed and rolled

Car 3: flipped completely

Cars 4–16: derailed in violent succession

Secondary explosions rippled through burning cargo.

Barb’s crew felt the shockwave through the hull.

The bomb worked flawlessly.

The railway was obliterated.

Repairs would take weeks.

Japan never discovered sabotage.

Investigators blamed:

faulty boilers

bad coal

poor maintenance

No one believed eight Americans had landed on their beach, planted a bomb, and vanished.

THE ESCAPE AND RETURN

Fluckey ordered Barb to dive.

They patrolled three more days, listening to frantic Japanese radio chatter.

Every message blamed mechanical failure—not sabotage.

Mission accomplished.

July 26th — Heading for Midway

After 48 days at sea, fuel low and crew exhausted, Barb turned toward home.

August 2nd — Arrival at Midway

They were greeted by officers, photographers, and stunned personnel who’d learned of the mission.

The eight saboteurs underwent long debriefings.

Hatfield explained the pickle-jar switch.

Saunders described the landing plan.

Walker detailed the transit.

The Navy knew this had been a breakthrough.

A submarine—without torpedoes—had crippled enemy infrastructure on land.

AFTERMATH AND HONORS

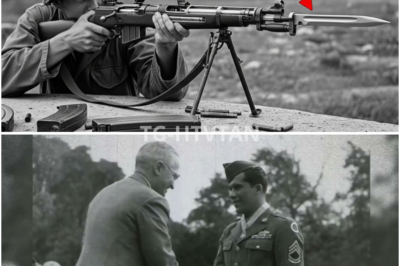

September 18th, 1945 — Pearl Harbor

Japan had surrendered a month earlier.

Fluckey received his fourth Navy Cross.

He already held the Medal of Honor for his previous patrol:

the one where he attacked 30 ships in Namkwan Harbor, in waters so shallow the hull scraped rocks.

That patrol had been history-making.

The train operation made him legendary.

WHAT HAPPENED TO THEM ALL

Commander Eugene “Lucky” Fluckey

Stayed in the Navy 27 more years

Rose to Rear Admiral

Directed Naval Intelligence

Served as advisor to Portugal

Retired 1972

Passed away 2007 at age 93

Buried at the Naval Academy

Under his command, USS Barb never suffered a single combat casualty.

Not one Purple Heart was awarded.

The Landing Party

Most returned to civilian life quietly.

Billy Hatfield

Electrician for 40 years. Rarely discussed the war.

Paul Saunders

Retired Navy chief petty officer in 1955. Barb was the highlight of his career.

Lt. William Walker

Became a California lawyer. Attended submarine reunions but seldom spoke of Karafuto.

USS Barb

Sold to Italy in 1954

Renamed Enrico Tazzoli

Scrapped in 1972

Battle flag preserved at Submarine Force Museum

Will live on as the name of a future Virginia-class submarine: SSN-804

The flag includes a symbol no other submarine displays:

a locomotive.

The only train ever destroyed by a submarine in naval history.

THE REAL LEGACY

American submarines:

Sank 1,200+ Japanese merchant ships

Destroyed 30% of Japan’s navy

Strangled the wartime economy

But the story of USS Barb stands out.

Eight ordinary sailors.

A homemade bomb.

A submarine commander who refused to lose a man.

And the courage to bring the war onto Japan’s shore for the first—and only—time.

Hatfield’s switch detonated at 2:47 a.m. on July 23rd, 1945.

Three weeks later, Japan surrendered.

The train explosion didn’t end the war.

But it symbolized everything that made the U.S. submarine force extraordinary:

Ingenuity.

Audacity.

Precision.

Leadership.

And courage.

News

My husband, unaware of my $1.5 million salary, said: “Hey, you sickly little dog! I’ve already filed the divorce papers. Be out of my house tomorrow!” But 3 days later, he called me in a panic…

My husband, unaware of my $1.5 million salary, said: “Hey, you sickly little dog! I’ve already filed the divorce papers….

At My Own Wedding, My Dad Took The Microphone, Said: “Raise Your Glass To The Daughter Who Finally Found Someone Desperate Enough To Marry Her.” People Laughed. My Fiancé Didn’t. He Opened A Video On The Projector And Said: “Let’s Talk About What You Did Instead”

“Raise your glass to the daughter who finally found someone desperate enough to marry her.” My father said that into…

At my wedding, my future in-laws mocked my mother in front of 204 people. Then they told another guest, “That’s not a mother. That’s a mistake in a dress.” My fiancé laughed. I didn’t. I stood up and canceled the wedding right in front of everyone. Then I did THIS. The next day, their entire world collapsed because…

At my wedding, my future in-laws mocked my mother in front of 204 people. Then they told another guest, “That’s…

ch1 They Sent 2 American Soldiers Against 300 Japanese — The Result Became A Legend Nobody Expected

THE ASSAULT ON PACO STATION — THE STORY OF CLETO RODRIGUEZ AND JOHN REE At 8:42 a.m. on February 9th,…

At Christmas, my mother-in-law looked at my six-year-old daughter and said, “Kids born from your mother’s cheating don’t get to call me Grandma.” She said it right after refusing the gift my daughter had made for her. Then my son stood up and said something. And suddenly, the whole room went silent — frighteningly silent…

At Christmas, my mother-in-law looked at my six-year-old daughter and said, “Kids born from your mother’s cheating don’t get to…

On Christmas Day, I was working a double shift in the emergency room. My parents and my sister told my 16-year-old daughter that “there wasn’t a seat for her at the table.” She had to drive home by herself and spend Christmas alone in a silent house. I didn’t argue. I acted. The next morning, my parents discovered a letter on their doorstep — and they started screaming the moment they read it…

On Christmas Day, I was working a double shift in the emergency room. My parents and my sister told my…

End of content

No more pages to load