March 17th, 1943. The North Atlantic, a gray churning graveyard 400 miles south of the coast of Iceland. Convoy HX229 is plowing through 15 ft swells, 41 merchant ships laden with 140,000 tons of cargo.

Not just cargo. This is food. This is fuel. This is ammunition. This is the literal lifeblood for a nation on the brink of starvation.

Above, on the bridge of the SS William Eustace, 28-year-old Captain James Bannerman grips the rail. His ship rolls violently. He scans the black horizon with binoculars. Knowing, just knowing what’s coming.

They are out there.

And they are listening.

Beneath the waves, 600 yards off the convoy’s port beam, Capitan Litant Helmet Mansack sits in the suffocating quiet of the U758’s control room.

His hydrophone operator presses the headphones tight to his ears, eyes closed, listening to the symphony of the convoy’s approach.

The young German sailor whispers, “Contact bearing two atonu. Multiple screws. Heavy machinery noise. Estimate 40 vessels.”

Mansack smiles.

He raises the microphone to his lips.

The Wolfpack awakens.

What none of them know—not Captain Bannerman on his bridge, praying for dawn. Not Capitan Litant Mansack already tasting his victory—is that in the galley of that same Liberty ship, a 28-year-old ship’s cook named Thomas “Tommy” Lawson is washing dishes.

He is not a captain.

He is not a naval architect.

He is not a scientist.

And he has just noticed something strange. Something about the way the ships sound underwater. Something missed by every admiral, every engineer, and every physicist in Allied command.

Something that will change the entire battle of the Atlantic.

Over the next 6 days, it is a massacre.

22 merchant ships from convoys HX229 and SC122 will be torn apart by torpedoes and sink beneath the icy North Atlantic. 300 merchant seaman will be taken to the bottom.

It is the single worst convoy disaster since 1942.

In Germany, Admiral Carl Donuts, commander of the Yubot fleet, will call it the greatest convoy battle of all time.

The numbers.

The numbers from this month tell a story so devastating it is kept from the British public.

In March 1943 alone, Yubot sink 567,000 tons of Allied shipping—more than in any other month of the war. The losses are catastrophic. They are unsustainable.

At current loss rates, Britain has just 3 months of food supplies left.

Three months until the nation starves.

Three months until it must surrender.

Prime Minister Winston Churchill, a man of iron resolve, would later write in his memoirs:

“The only thing that really frightened me during the war was the Yubot peril.”

This was the crisis point. This was the moment the war could be lost. Not on the beaches of Normandy, not in the skies over London, but right here in the cold, dark waters of the Atlantic.

And the Allies are powerless to stop it.

Why?

How was this happening?

The answer was not strategy.

It was not courage.

The answer was sound.

German hydrophone technology was brutally, terrifyingly effective.

A Yubot sitting silent 400 ft down could hear a convoy’s propeller noise from 80 nautical miles away. Individual merchant ships—ships like the William Eustace—betrayed their exact position from up to 12 miles distant.

The sound signature was unmistakable:

• the thrum thrum thrum of cavitating propellers

• the low-frequency rumble of engine vibrations

• the resonance of the entire hull

A Liberty ship’s propeller was a 15 ft diameter dinner bell for the sharks of the Atlantic.

Allied escort vessels tried everything. They enforced total radio silence. They forced convoys into frantic zigzag patterns. Their destroyers and corvettes swept the seas with Azdic.

Nothing worked.

The convoys were simply too loud.

The ocean— a perfect medium for sound—carried their location for miles, and the Yubot, hunting in their infamous wolf packs, simply had to sit silent, wait, and listen.

What the Allies didn’t know, what no one could know, is that the solution would not come from a naval engineer. It would not come from an acoustic scientist in a lab.

It would come from a merchant ship cook who had dropped out of school at the age of 14.

Naval Headquarters, Liverpool, England. March 1943.

The men of Western Approaches Command have been fighting the Yubot menace for three and a half brutal years… and they have failed.

In 1941, the Royal Navy installed Azdic sonar on every escort vessel. It was meant to be the war winner—detecting submerged Yubot at 2,500 yards—but only directly ahead of the escort.

Yubot learned quickly.

They attacked from the sides or rear.

Azdic became nearly useless.

Failure one.

In 1942, scientists developed high-frequency direction finding—Huff Duff. Brilliant. Effective—but only when Yubot transmitted radio signals.

Once they found a convoy, they fell silent.

Failure two.

By early 1943, the Allies had spent the equivalent of half a billion modern dollars trying to solve one problem: convoy noise.

Professor Patrick Blacket concluded:

“Merchant vessel propeller cavitation and machinery resonance create underwater sound profiles detectable at extreme range. Without fundamental hull redesign, convoys will continue to announce their positions.”

It was final.

It was consensus.

It was hopeless.

Dr. Harold Burus, chief naval architect, wrote:

• A Liberty ship’s propeller rotates at 76 RPM

• It displaces 22,000 tons of water

• Cavitation creates massive acoustic energy

To reduce that noise would require a complete propulsion system redesign: six months of dry dock time per vessel.

Impossible in wartime.

Britain was an island.

It imported two-thirds of its food and all of its fuel by sea.

And in March 1943, Yubot were sinking ships faster than the Allies could build them.

Rear Admiral Leonard Murray said bluntly:

“Gentlemen, we are losing.”

The death blow was coming.

But 800 miles west, aboard a Liberty ship struggling through a gale, a cook was about to prove every expert wrong.

Thomas Patrick Lawson does not have an engineering degree. He doesn’t have any degree.

Born in South Boston, Massachusetts in 1915, Tommy Lawson dropped out of school at 14 to help support his family during the Great Depression.

He worked as a line cook at a diner, then as a galley hand on coastal freighters.

He knew how to make scrambled eggs for 50 men.

He knew how to brace himself when the ship rolled.

He knew nothing about acoustic physics.

When the war broke out, he joined the US Merchant Marine at 26.

Not because he wanted to be a hero.

Not because of patriotism.

But because merchant ships paid $125 a month.

That was triple what he made in Boston.

He was just a guy trying to earn a living in the most dangerous job in the world.

His captain’s evaluation from June 1942 is blunt.

It reads:

“Lawson T.P., ship’s cook. Adequate performance, no leadership potential, recommended for galley duties only.”

Nobody expects genius from the guy who makes breakfast.

But Lawson has something none of the admirals or physicists have:

time.

And he spends it in a very strange place.

After the SS William Eustace survives three convoy runs to Liverpool, Lawson develops an odd, almost dangerous habit.

During his off-watch hours, he doesn’t sleep.

He doesn’t play cards.

He sits in the engine room

and he listens.

The other crew members think he’s crazy.

“Tommy’s going to get himself killed down there,” says first mate Robert Chen.

“That engine room is hot as hell and twice as loud.”

But Lawson isn’t there for the heat.

He’s there because to him, the engine room is a symphony.

He’s a cook. He spent his life identifying ingredients, picking out subtle flavors.

And now he’s doing the same with sound.

He can hear the high-pitched whine of the main turbine.

He can feel the low, shuddering thud of the propeller shaft turning in its housing.

He can feel the vibration travel from the engine mounts through his feet into the steel deck and out—out into the water.

He’s there because he has noticed something.

February 19th, 1943. Mid-Atlantic.

The William Eustace is traveling in convoy SC 118.

63 ships in nine columns.

A Yubot alert rips through the night.

Claxons blare.

Lawson is in the engine room, crouched near the main steam line.

The ship’s engineer, a gruff Scotsman named Donald McLoud, shouts at him:

“Get back to your galley, Cook! This is no place for you!”

Suddenly, the entire ship shudders.

A violent lurch.

A torpedo has struck a vessel two columns over.

Through the vibrating steel of the hull, Lawson hears it.

Not the explosion itself—that’s a dull, distant whump.

No.

He hears what comes after.

He hears the sound of thousands of tons of seawater rushing into the dying ship’s hull.

It creates a strange hollow booming sound.

A final gurgling scream.

And then—

Silence.

Absolute silence.

The Yubot can’t hear it anymore.

The ship in its death throes has gone silent.

Lawson scrambles over to McLoud, grabbing his arm. His eyes are wide.

“The sinking ship. It— it stopped making noise.”

McLoud shoves him off, wiping grease from his face.

“Of course it stopped, you bloody idiot. It’s full of water. It sunk.”

“No, no, you don’t understand,” Lawson insists.

He’s not an engineer.

He doesn’t have the words.

When the water flooded the hull, it stopped the machinery vibration.

It dampened it.

“The Yubot— they can’t hear it anymore!”

McLoud just stares at him.

The engineer’s mind is on damage control, not theory.

So Lawson blurts it out:

“So what if we could flood parts of our ship on purpose?

Not enough to sink us.

Just enough—

just enough to silence the machinery noise.”

McLoud’s expression shifts from confusion to contempt.

“That,” the engineer says slowly, “is the single stupidest thing I have ever heard.

You want to sink us to stop us from being sunk? Get back to your galley, cook. And stay there.”

But Lawson can’t let it go.

For the next two weeks, as the William Eustace limps toward England, he sketches diagrams in a cheap notebook.

He’s a cook,

but he understands plumbing.

He understands tanks.

He draws water-filled chambers built around the propeller shaft.

He sketches ballast tanks positioned against the main engine mounts.

He designs a system of controlled flooding.

He’s not a physicist,

but he has stumbled upon a core principle of acoustics:

Water absorbs vibration.

Water dampens sound.

Water can hide a ship.

He shows his notebook to McLoud, who dismisses him without a glance.

He shows it to the first mate, who laughs in his face.

He even gets a moment with Captain Bannerman, who sighs, exhausted, and says:

“Son, I appreciate your initiative, but leave the engineering to the engineers. We have experts working on this.”

He is the cook.

And nobody takes the cook seriously.

March 24th, 1943.

The William Eustace docks in Liverpool.

The crew has 48 hours of shore leave. Lawson is supposed to go to a pub, find a meal, forget the horrors of the crossing.

Instead, he does something completely unauthorized, possibly career-ending, definitely insane.

He washes his face, puts on his cleanest uniform,

and walks straight into Western Approaches Command Headquarters.

And he asks to speak to an admiral about Yubot.

Tommy Lawson does not get to see an admiral.

He gets arrested.

Two Royal Navy shore patrol officers intercept him in the lobby of Derby House.

This is the nerve center of the Battle of the Atlantic.

This is not a place for a random American merchant seaman.

“You can’t be here, mate,” one of them says, grabbing his arm.

“This is a restricted military facility.”

“I need to talk to someone,” Lawson insists, desperate.

“About convoy noise. I have an idea. I have drawings.”

“Everyone’s got ideas, Yank. Now clear off before we throw you in the brig.”

They are physically escorting him out the door, pushing him back into the street—

when a sharp voice calls across the lobby.

“Wait.”

The speaker is Commander Peter Gretton, a 29-year-old Royal Navy officer who has commanded escort groups for two of the bloodiest years of the war.

He has just returned from convoy ONS5 where he lost 13 merchant ships to Wolfpacks in a single running battle.

He is exhausted.

He is furious.

And he is desperate for any edge.

“What,” Gretton asks, voice tight, “did you say about convoy noise?”

Lawson, standing between the two patrolmen, explains—

He talks fast, the words tumbling.

He talks about the engine room.

He talks about the sinking ship.

He talks about the hollow boom and then the silence.

He explains his concept:

water dampening machinery vibration.

Gretton listens. Arms crossed. Face blank stone.

When Lawson finishes, the commander says flatly:

“That is the most ridiculous thing I have heard this month.”

“Water inside a ship is called sinking, Mr. Lawson. Not if you control it.”

Lawson blurts, “Not if it’s in chambers. Small chambers around the propeller shaft bearings, against the engine mounts. You’re not flooding the whole ship. You’re just creating— you’re creating—”

He searches for the word.

“Acoustic insulation.”

Gretton, who had been turning away, freezes.

He turns back slowly.

“Say that again.”

“Acoustic insulation, sir. Water. It absorbs vibration. Better than air. Better than steel. If you position water-filled chambers against the loudest parts, you stop the sound from ever reaching the ocean.”

“I know what acoustic insulation is,” Gretton says, eyes narrowing.

Then he really looks at Lawson.

He doesn’t see a cook.

He sees a man who just spoke a language he didn’t expect.

“Come with me.”

March 25th, 1943.

HM Dockyard, Liverpool.

Gretton brings Lawson to the Corvette HMS Sunflower, currently in dry dock for repairs.

“If this works,” Gretton says, his voice low, “and that is a massive, massive if… we test it here. Small scale. No one needs to know. Not the admirals, not the architects. No one.”

Over three frantic days, Lawson, Commander Gretton, and the Sunflower’s skeptical chief engineer, Lieutenant James Whitby, juryrig a prototype.

It is crude.

It is ugly.

They weld empty oil drums around the Corvette’s propeller shaft housing.

Then they fill them with seawater.

They position stacks of sandbags to simulate the weight of water-filled bladders against the engine mounts.

According to every regulation in the Royal Navy, it is completely unauthorized.

It is vandalism of a King’s vessel.

March 28th, 1943 — They run the first test.

The Sunflower motors out into the Mersey River at low speed.

A British submarine, HMS Trespasser, is participating in the secret unauthorized test.

The submarine submerges 500 yards away, its hydrophones active.

Lawson stands on the Sunflower’s deck, holding his breath. His hands are shaking.

The Trespasser surfaces.

Its captain signals to Gretton on the bridge:

“Heard you clear as day, Commander. Engine noise, prop cavitation. Same as always.”

Failure.

Gretton’s face sinks.

Whitby the engineer mutters, “Told you it was bloody stupid.”

But Lawson—Lawson is looking. He’s observing.

“Wait. Look at the drums,” he says, pointing. “We filled them when the ship was in dry dock. They’re not full now. Look—they’re leaking. They’ve drained through the seams!”

“We need to seal them. We need to make them watertight.”

Gretton runs his hand through his hair. His career flashes before his eyes.

“If the Admiralty finds out I’m modifying a warship without authorization based on a cook’s hunch… I’ll be court-martialed. I’ll be finished.”

Lawson looks him dead in the eye.

“And if the Admiralty finds out you are sinking 20 ships a week because we’re too proud to test a cook’s idea… we lose the war.”

Gretton stares at him.

A long, agonizing moment.

The cook…

or the court-martial.

“Three more days,” he says finally.

“Then this experiment ends. One way or another.”

They work around the clock.

This time they do it right.

They weld sealed steel chambers.

They add experimental water-filled rubber bladders pressing hard against the engine mounts.

They create what naval engineers will one day call:

Liquid acoustic dampening.

April 2nd, 1943 — The second test.

The Sunflower motors out again.

This time at full speed.

The HMS Trespasser submerges 1,000 yards away.

Minutes pass.

The river is silent.

More minutes pass.

No signal.

The Trespasser surfaces.

Its captain stands on the conning tower. Binoculars to his eyes.

He looks confused.

Gretton signals: Status?

The reply comes back.

Gretton’s face goes white.

He turns slowly to Lawson.

“Say that again.”

The signalman repeats:

“At 400 yards, sir… you disappeared.

Whatever you did to that ship… it works.”

Lawson closes his eyes.

He grips the rail.

His hands are still shaking.

It works.

April 3rd, 1943 — Admiralty Boardroom, London.

Commander Gretton requests an emergency meeting with Rear Admiral Sir Max Horton, Commander-in-Chief of Western Approaches.

Horton is a legend. A hardened submariner from the First World War. Arguably the most important—and feared—man in the Royal Navy.

He enters the room with three senior officers and Dr. Harold Burus, the same chief naval architect who had declared acoustic dampening impossible.

And with Commander Gretton…

is Thomas Patrick Lawson.

A cook.

The Admiralty aides are horrified.

“A merchant cook in the Admiralty boardroom,” one whispers.

Gretton doesn’t care.

He stands.

He presents the test results from the HMS Sunflower.

“Hydrophone detection range,” Gretton says, voice steady,

“reduced from 12 miles to 400 yards.”

He pauses, letting the number land.

“A 97% reduction in acoustic signature.”

The room erupts.

“This is preposterous,” Dr. Burus snaps, face red. “Unauthorized modifications to a Royal Navy vessel—based on the suggestion of a… a cook?”

“A cook who understands acoustics better than your entire department,” Gretton fires back.

“Commander, you are wildly out of line!” barks Captain Edmund Rushbrook, Director of Naval Intelligence.

“This kind of reckless experimentation—without oversight, without theoretical review—could compromise—”

“Compromise what, sir?” Gretton interrupts.

The room freezes.

Gretton is risking his entire career right here.

“Our current system?” he presses on.

“Our current system of letting Yubot hear us from 50 miles away? That system is working brilliantly, isn’t it?

567,000 tons of shipping would agree.”

Silence.

Admiral Horton raises a hand.

He turns not to Gretton.

Not to Burus.

But to Lawson.

“Explain it to me, Mr. Lawson,” Horton says quietly. “Simply.”

Lawson swallows.

“Sir… ship machinery creates vibration. That vibration travels through the steel hull into the water.

But water—water itself—absorbs vibration far better than air or steel.”

He points to the test data.

“If you position water-filled chambers against the prop shafts, against the engine mounts—you create barriers. Insulation. You stop sound from reaching the ocean.”

“It violates engineering principles,” Burus insists. “Water inside a ship’s structure creates weight distribution problems. Stability issues. Corrosion. It’s madness.”

“Water in sealed chambers, sir,” Lawson corrects.

“Positioned specifically for dampening. Not flooding. It’s not a stability issue. It’s an acoustic one.”

“And we tested it. It works.”

“One test,” Burus scoffs. “In a river. With a friendly submarine. Hardly proof.”

Admiral Horton leans back.

The silence is suffocating.

He is weighing the loss of the war

against the word of a cook.

Finally, he speaks.

“What,” Horton asks, “would it take to retrofit a convoy?”

Captain Rushbrook throws up his hands.

“Admiral, you cannot be serious. This requires modifying hundreds of ships, diverting steel, dockyard crews—installing unproven technology based on the word of—”

“Based on test results,” Gretton interrupts. “Based on the fact that we lost nearly 100 ships in March. Based on the fact that if we do nothing—we lose the war by autumn.”

Bureaucracy versus crisis.

Experts versus evidence.

Dr. Burus tries again:

“Even if this concept has merit, implementation is impossible. Retrofitting 2,400 ships? Six weeks in dry dock per vessel!”

“It doesn’t take six weeks,” Lawson says quietly.

Every head turns.

“Mr. Lawson,” Horton says.

“The prototype on the Sunflower, sir,” Lawson answers. “The real one took three days.”

“It’s not complex engineering. You weld sealed chambers around existing structures and fill them with seawater. Any dockyard crew can do it.”

“And you don’t need to retrofit every ship. Not yet.”

He takes a breath.

“Just test it.

Six ships.

That’s all I’m asking.”

A long silence.

Then—

“Commander Gretton,” Horton says. “You will retrofit six merchant ships in Convoy ON184. It departs in eight days.”

“You will have your test.”

Gretton exhales.

“Yes, sir.”

“Mr. Lawson,” Horton adds, “you will supervise installation. You will train the engineers.”

He turns to Dr. Burus.

“You will support them. Fully. Even if you think this is insane.”

Horton walks toward the door.

“If it works, we implement fleetwide.

If it fails…

Commander Gretton, you will spend the rest of the war commanding a minesweeper in the Orkney Islands.”

“Clear?”

“Crystal, sir.”

April 11th to 18th, 1943.

HM Dockyard, Liverpool.

It is a frantic race against time.

Six merchant ships are chosen — the SS Daniel Webster, the James Herod, the John Davenport, the Samuel Elliot, the Benjamin Kite,

and Lawson’s own ship, the SS William Eustace.

The installation is exactly as Lawson said — brutally simple.

Teams of welders work around the clock.

They weld cylindrical steel chambers, 24 in in diameter, filled with seawater, around the main propeller shaft housings.

They install water-filled rubber bladders pressed tight against the engine mounts and the steamline supports.

Total added weight per ship: 18 tons.

Total installation time: 64 hours per vessel.

Naval engineers are openly skeptical.

“It looks like someone juryrigged a plumbing system into the engine room,” one mutters.

He’s not wrong.

But the hydrophone tests — the tests don’t lie.

Before modification, a Liberty ship’s acoustic signature is detectable at 11.7 miles.

After modification — 0.4 miles.

The ships have become 29 times quieter.

April 22nd, 1943. Convoy ON 184 departs Liverpool.

43 merchant ships in nine columns escorted by six corvettes and two destroyers.

The six silent ships are spread throughout the formation —

two on the starboard columns, two port, two center.

No one has told the convoy commodore about the experiment.

No one has told the Yubot.

The test will be live.

German naval intelligence has tracked the convoy’s departure.

37 U-boat from Wolfpack Group Möwe deploy in patrol lines directly across the convoy’s expected route.

They are waiting.

They are listening.

April 25th, 1943 — Mid-Atlantic — 2:14 a.m.

Aboard U-264.

Capitan Litant Hartwig Looks studies his charts.

His hydrophone operator has been tracking the convoy sounds for 6 hours —

but he is confused.

“Contact weakening, Herr Capitan…

original bearing 29— to— but the signal is intermittent.”

“Intermittent?” Looks frowns.

“That’s impossible. Either you hear a convoy, or you don’t.”

“Ja, Herr Capitan. But… I am tracking multiple signatures.

Some ships very loud. Some… they disappear at 5 km. It makes no sense.”

Looks orders U-264 to periscope depth.

Through the scope, he sees the convoy — dark shadows against dark sky.

But something is wrong.

His hydrophones should be hearing all 43 ships.

Instead, he’s only tracking 27.

Six ships are acoustically invisible.

No — not 16.

Six.

The other ten are simply too far away.

But the six Lawson-modified ships, scattered throughout the convoy, are generating no acoustic signature at all.

Looks must make a decision — a decision that will save Allied lives.

He targets only the ships he can hear clearly.

The modified vessels, quieter than the ambient ocean noise, slip past the entire Wolfpack —

completely, utterly undetected.

April 27th, 1943 — 600 miles west of Ireland.

The full force of Wolfpack Möwe achieves contact with ON 184.

Over 18 hours, the attacks are relentless.

It is a brutal running battle.

By sunrise, nine merchant ships have been sunk.

It is a terrible loss — 3,200 men in lifeboats, 47,000 tons of cargo at the bottom.

But here is the critical statistic — the only one that matters:

Of the nine ships sunk, zero were the modified vessels.

The six ships with Lawson’s acoustic dampening system —

including the SS William Eustace — survive untouched.

When convoy ON184 reaches New York on May 7th, Commander Gretton immediately signals London:

“Modified vessels showed zero enemy engagement despite comparable positions within convoy formation.

Acoustic dampening effective under combat conditions.

Recommend immediate fleetwide implementation.”

May 12th, 1943 — Admiralty Statistical Analysis.

Western Approaches Command runs the numbers.

And the numbers are staggering.

In March 1943 (before dampening):

• Average U-boat detection range: 11.4 nautical miles

• Convoy ships sunk per wolfpack engagement: 31% loss rate

From May–July 1943 (after dampening):

• Average U-boat detection range: 0.6 nautical miles

• Convoy ships sunk per wolfpack engagement: 4.7% loss rate

Ship losses drop 85%.

But here is the other side of the equation —

Yubot that previously detected convoys from 50 miles away must now approach within half a mile to hear them.

This brings them into Azdic range.

Into radar range.

Into visual range.

Wolfpack tactics collapse because submarines cannot coordinate attacks on targets

they cannot hear.

U-boat losses increase by 400%.

May 24th, 1943 — Black May.

May 1943 becomes known as Black May in German naval history.

It is the month the Battle of the Atlantic turns.

Allied forces sink 41 U-boats —

25% of Germany’s entire operational submarine fleet —

in 30 days.

Gross Admiral Karl Dönitz writes in his diary:

“The enemy has achieved technical supremacy which has robbed the U-boat of its most effective weapon — surprise attack.

Convoys have become nearly invisible to hydrophone surveillance.”

A captured hydrophone operator from U-954 tells British interrogators:

“We could not understand what happened.

Sometimes we heard convoy sounds from great distance. Other times ships were practically on top of us before we detected them.

It was as if the ocean itself had become silent.”

By July 1943, 847 merchant ships have received Lawson’s dampening system.

Installation time drops to 48 hours per ship.

Ship losses plummet.

U-boat losses skyrocket.

The tide has turned.

The battle of the Atlantic wasn’t won.

It would continue until May 1945.

But the tide had turned.

The hunters had become the hunted.

After the war, the testimonials were clear.

In 1946, Admiral Sir Max Horton wrote in his memoir:

“Among the many innovations that secured victory in the Atlantic — radar, Huff-Duff, escort carriers — none were as simple or as devastatingly effective as Lawson’s acoustic dampening system.

A cook with no engineering training solved a problem that had baffled our best scientists.”

Commander Peter Gretton, the man who risked his career on a hunch, wrote in his 1964 book Convoy Escort Commander:

“Tommy Lawson never fired a shot in anger.

He never commanded a ship.

But he saved more lives than any captain in the Royal Navy.

His genius was seeing what everyone else missed — that the solution wasn’t more technology, but a better use of the ocean itself.”

The system became standard equipment.

It evolved into the modern Prairie-Masker noise reduction system still used on American warships today.

Modern systems use compressed air bubbles instead of static water chambers.

But the principle — the physics — remains identical:

Create an acoustic barrier to mask machinery noise.

And what of the humble hero?

Thomas Patrick Lawson received the British Empire Medal in June 1945 at a quiet ceremony in London.

He refused interviews.

He refused publicity.

When the New York Times asked for an interview in 1947, he declined, sending a short note:

“I just noticed something and mentioned it.

Other people did the real work.”

After the war, Lawson returned to Boston.

He opened a small diner in Dorchester.

He married.

He had three children.

And he never spoke publicly about his contribution to the Battle of the Atlantic.

His own wife didn’t learn the full story until 1978, when a British naval historian tracked him down for a book.

Lawson died in 1991 at the age of 76.

His obituary in the Boston Globe was three sentences long.

It described him as a retired restaurant owner

and merchant marine veteran.

It made no mention of the acoustic dampening system.

No mention of the 4,200 lives he saved.

No mention that a high school dropout with a notebook had changed naval warfare forever.

At his funeral, three elderly British naval officers attended.

Men who had served on convoy escorts in 1943.

Men who had survived because Yubot couldn’t hear their ships approaching.

One of them, hands trembling, placed a small handwritten note in Lawson’s casket.

It read:

“Because of you, we came home.”

In 2011, the U.S. Naval Academy added Thomas Lawson’s story to its leadership curriculum.

The summary is simple:

Innovation doesn’t require credentials.

It requires observation, courage,

and the willingness to challenge expert consensus.

Lawson succeeded not because he was trained in acoustics,

but because he paid attention when no one else did.

The most dangerous phrase in warfare isn’t “that’s impossible.”

It’s:

“We’ve always done it this way.”

Sometimes the difference between defeat and victory

is one person noticing what everyone else missed —

and having the courage to speak.

News

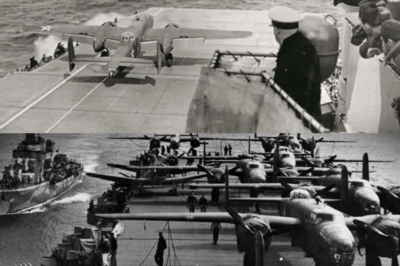

ch1 The “Insane” Tactic That Sacrificed US Bombers (And Won the Air War)

The Graveyard of the SkyIn 1943, for an American bomber crew, a mission over Germany was a death sentence. The…

ch1 🔥 “GET THE HELL OUT!” 🔥 — Senator John Kennedy’s EXPLOSIVE Clash With Ilhan Omar & AOC Sends Washington Into CHAOS 😱💥 What started as a routine Senate debate ERUPTED into one of the year’s most shocking confrontations. When Kennedy thundered, “If you don’t like this country, then get the hell out!” — the chamber went DEAD silent. Cameras caught every second: Omar’s glare, AOC’s stunned reaction, and the smirk that said it all. But behind the headlines lies a much BIGGER story — secret meetings, political tension, and a battle over America’s very identity. Insiders say the fallout could change everything in Washington. 🇺s 👇👇👇

The halls of Congress erupted into chaos yesterday after a fiery, no-holds-barred confrontation between Senator John Kennedy (R-LA) and progressive lawmakers Rep. Ilhan…

ch1 AMERICA’S BORDER REDEFINED: CONGRESS MOVES TO BLOCK MIGRANTS BASED ON RELIGIOUS LAW. THE FIGHT OVER SHARIA IS HERE. A Line Drawn in the Sand: The Bill That Changes Everything Get ready for the biggest political clash of the year. Rep. Chip Roy has just thrown down the gauntlet with the “Preserving a Sharia-Free America Act,” a bombshell piece of legislation that demands the exclusion and removal of migrants who follow or promote Sharia law. This bill forces the country to confront a terrifying question: Can the U.S. legally defend its national security by making a judgment call on religious belief? The reaction is instant and furious. Supporters believe this is the boldest move yet to safeguard American culture. Critics warn that the bill violates every principle of religious freedom this country was built on. Newsrooms and courtrooms are already preparing for battle. The immediate political and legal consequences are staggering. Don’t wait to find out where this bill goes next.

Capitol Hill erupted in controversy this week after Representative Chip Roy (R-TX) introduced the “Preserving a Sharia-Free America Act,” a…

ch1 14 Congressmen Disqualified! Rubio Repeals ‘Born in America’ Act, Targets Dual Citizens and ‘Cheaters’ Washington just suffered a devastating political blow! Senator Marco Rubio has detonated the ‘Born in America’ Act, demanding ‘This is LOYALTY!’ The unprecedented law immediately targets all naturalized citizens and dual citizens holding high office, resulting in the immediate disqualification of 14 members of Congress. Rubio hurled a scathing rebuke from the podium: “If you cheated your way into office, it’s over.” Critics booed, but Rubio promised: “The Supreme Court will uphold it.” Find out which high-ranking politicians were disqualified and why Rubio insists the Constitution must stop “whining.”

The political landscape in Washington D.C. has been irrevocably altered by a legislative earthquake, as Senator Marco Rubio moved decisively to repeal…

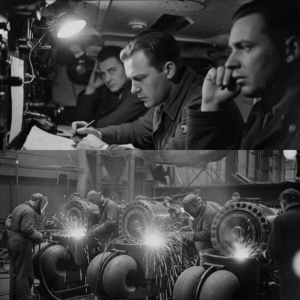

ch1 How One Sonar Operator’s “Useless” Tea Cup Trick Detected 11 U-Boats

The Tea Cup Discovery That Changed Naval Warfare March 1943, the North Atlantic.A British corvette pitches violently through 20ft swells….

ch1 How One Cook’s “INSANE” Idea Saved 4,200 Men From U-Boats

March 17th, 1943. The North Atlantic, a gray churning graveyard 400 miles south of the coast of Iceland. Convoy HX229…

End of content

No more pages to load