The other Allied commanders thought he was either lying or had lost his mind. The Germans were laughing, too. Hitler’s surprise attack had just ripped a vast hole through Allied positions in the Arden, creating what the press would soon call the Bulge. Vermuck commanders were convinced they had accomplished the impossible. Total strategic surprise against the overconfident Americans. They believed their winter offensive would sever the Allied armies and force a peace treaty. After all, who could possibly halt three German armies comprised of 250,000 troops and 1,000 tanks surging through frozen woods toward Antworp? But the Germans didn’t know about George Patton. And they certainly didn’t expect that in the coldest winter in recent memory, with temperatures plunging below freezing, this American general would not only halt their charge, but turn their ambitious offensive into their ultimate disaster on the Western Front. This is the account of how Patton’s third army turned the snow crimson with enemy casualties and transformed Hitler’s final gamble into America’s most significant battlefield victory.

Lieutenant General George Smith Patton Jr. was 59 years old when fate called him to the Arden. Born into a military lineage in 1885, Patton had dedicated his life to preparing for the moment when everything would depend on one man’s capability to guide soldiers into the severity of modern war. By December 1944, he commanded the Third Army, consisting of over 250,000 men and hundreds of tanks, and had already cemented his fame as the most aggressive tank commander in the Allied forces. But December 16th, 1944 altered everything.

While Patton’s third army was advancing through the SAR region, preparing for their own thrust into Germany’s industrial corps, Hitler launched operation watch on the Rine. In the pre-dawn darkness, 29 German divisions slammed into the lightly defended American lines in the Arden Forest. The German strategy was daring in its scope. Drive 60 mi through Belgium and Luxembourg, seized the crucial port of Antwerp, and split the British and American forces.

What made the German assault so astonishing was not just its scale, but its timing. Allied intelligence had completely failed to spot the enormous concentration of German forces. The Vermarked had moved 250,000 men and 1,000 tanks into position, relying only on nighttime movements and strict radio silence. When the attack commenced, it achieved total tactical surprise. Within hours, German armored units were speeding westward, overwhelming American positions and triggering chaos in Allied command centers.

The critical moment arrived on December 19th when General Dwight Eisenhower convened an urgent conference at Verdan. The situation was dire. German forces had already pushed 20 m into Belgium, imperiling strategic intersections and the vital town of Bastonia. The first army was in chaos with entire units fragmented or decimated. If the German drive continued at this velocity, they might actually reach Antworp and secure their strategic goal.

To grasp what transpired next, you must understand the individual who would determine the battle’s result. George Patton had been training for this instant his entire military career. As a young officer, he had studied the great military leaders of history, Napoleon, Alexander, Caesar, and believed he was destined to command a great army in a desperate conflict. His early experiences in World War I, where he led the first American tank formations in combat, taught him the crucial strength of armored warfare and rapid offensive maneuvers.

Yet, Patton’s road to the Arden was challenging. His spectacular leadership in North Africa and Sicily had been marred by the infamous slapping incidents where he physically assaulted two soldiers suffering from combat stress. This incident nearly ended his career and excluded him from the initial D-Day landings. However, his reputation for energetic leadership and strategic insight made him essential. The Germans feared him more than any other allied general. So much so that he became the centerpiece of a complex deception effort that convinced the vermach he was planning to invade at Calala instead of Normandy.

By the time the Third Army entered France in July 1944, Patton had learned to better manage his aggressive tendencies. His leadership method was unique among Allied commanders. While other generals directed their armies from secure command posts, Patton spent his days visiting frontline units, frequently riding in an open jeep through enemy fire. He recognized that soldiers needed to witness their commander sharing their peril and hardship.

The Third Army’s swift thrust across France had already showcased Patton’s tactical brilliance. After breaking out of Normandy, his troops had advanced 600 miles in just four months, freeing thousands of square miles of land and capturing hundreds of thousands of German prisoners. But the fall of 1944 brought frustration, supply shortages, and fierce German resistance in places like Mets had slowed his advance to a crawl. Many began to question if Patton was only a successful pursuit commander, effective when chasing a retreating foe, but less capable against determined opposition.

The Battle of the Bulge would prove that analysis entirely wrong. What Patton exhibited in the winter of 1944 challenged conventional military wisdom, the idea of impossible logistics becoming achievable through superior leadership and foresight. When Eisenhower asked him how long it would take to turn his third army north to counterattack, Patton’s response stunned everyone present. While other generals were still trying to comprehend the magnitude of the German offensive, Patton was already several steps ahead.

Unknown to the other commanders at Verdon, Patton had already considered this scenario. His intelligence staff had noticed unusual German activity and had drafted three separate contingency plans for a northward turn. This was Patton’s climax, his brilliance. He didn’t just react to events, he anticipated them. While others were taken back by the German offensive, Patton saw it as a prime opportunity.

The sheer scope of Patton’s proposal defied traditional military theory. He was offering to pull six full divisions out of active combat, turn them 90°, and march them over 100 m through some of the worst winter weather in decades, all while keeping their combat readiness intact. Most military experts would have labeled this unfeasible.

Moving an army while in contact with the enemy is one of the most challenging military maneuvers. Doing it in winter over frozen roads while maintaining secrecy seemed utterly impossible. But Patton understood something that manuals couldn’t teach. The force of audacious action to turn desperate situations into decisive victories. His principle was simple. Attack. Always attack. He believed the enemy was always weaker than they appeared and that rapid aggressive action could overcome nearly any disadvantage. This was not thoughtless courage. It was calculated aggression based on thorough preparation and an intimate understanding of his enemy’s limitations.

Hitler’s plan demanded precise timing and flawless execution. The German forces had limited fuel reserves, only enough for 6 days of operations, and relied on seizing Allied fuel depots to continue their advance. They needed to reach their objectives quickly before Allied air superiority could intervene and before American reinforcements could arrive. Any delay would guarantee the offensive’s failure.

Patton’s solution was simple in concept, but immensely complicated in execution. Instead of attempting to stop the German offensive where it was strongest, he would attack where they were most exposed, at the base of the bulge. His three division assault would not only relieve the surrounded garrison at Bastonia but also threatened to trap the entire German spearhead.

On December 19th, Patton departed the Verdon conference and immediately set his plan in motion. He contacted his headquarters and spoke just two words, playball. This code phrase activated the pre-arranged operational directives his staff had prepared. Within hours, over 133,000 Third Army vehicles were beginning one of the most complicated military troop movements in history. The Fourth Armored Division, the 81st Infantry Division, and the 26th Infantry Division started their march north, followed by support convoys transporting 62,000 tons of supplies.

The conditions they faced were beyond brutal. This was the coldest winter in living memory across Europe. Temperatures hovered around -7° C with snow that made visibility almost impossible. American troops lacked suitable winter attire. Many soldiers had only cotton field jackets and wool overcoats to shield them from the frigid conditions. Weapons seized up and required constant upkeep. Truck engines had to be started every half hour to prevent their oil from thickening.

But Patton had prepared for this moment in ways that went beyond mere logistics. He understood that winter combat was as much a battle of morale as it was of supplies. While other commanders took cover in heated headquarters, Patton made it a point to be visible to his troops. He constantly traveled in an open jeep, his only concession to the icy temperatures being a heavy winter parker. His face often froze, but he persisted in his daily inspections, ensuring that the news of his presence spread through the ranks.

The psychological effect was colossal. American soldiers fighting in conditions that would have challenged lesser units drew strength from knowing that old blood and guts was enduring their hardship. His words of praise and encouragement rapidly circulated through the Third Army’s communication network. The old man says, “We’re the finest soldiers in the world.” Or Georgie says, “This is our finest hour.” This was not just empty talk. Patton genuinely believed his soldiers were capable of the impossible and his self-belief became theirs.

German General Eric Brandenberger, commanding the German 7th Army facing Patton’s sector, had expected a rapid reaction from the enemy. He was aware of Patton’s reputation for aggressive armored warfare and had even acknowledged that Patton conducted operations according to the fundamental German conception of mobile warfare. But even Brandenberger was astonished by the speed and precision of the Third Army’s northward pivot. German commanders had not believed that any Allied force could perform such a complex maneuver under winter conditions. They assumed the Americans would struggle. They were wrong.

By December 1944, the Vermacht was no longer the force that had conquered Europe. Low supplies, poorly equipped troops, and strained logistics made it impossible to react quickly. Patton’s maneuver shattered German expectations and set the stage for one of the most decisive counterattacks of the war.

News

“He Left Me for Another Woman. How Do I Move On?”

About a year ago, I met a man – “Ryan” – who was on a work assignment in my town…

The restaurant manager knocked my water over and cleared my table for a famous actress. “This table is for celebrities, not for nobodies in t-shirts. Get out.” I texted the Board. Immediately, the head chef turned off the stoves and walked out with the entire staff. He bowed to me: “Boss, we are quitting as ordered. No one is cooking for that actress.”

L’Orangerie was never merely a restaurant. In the fevered imagination of Los Angeles, it was a cathedral, a sanctuary where the…

ch1 Japan Built an “Invincible” Fortress. The US Just Ignored It

In 1944, the Japanese Empire had a plan to win the war. It was simple, brutal, and based on centuries…

ch1 How One Sonar Operator’s “Useless” Tea Cup Trick Detected 11 U-Boats Others Missed — Saved 4 Convoys

March 1943, the North Atlantic.A British corvette pitches violently through 20ft swells. Spray crashing over her bow every few seconds….

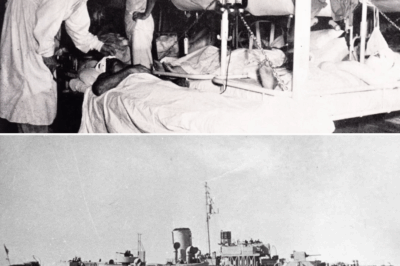

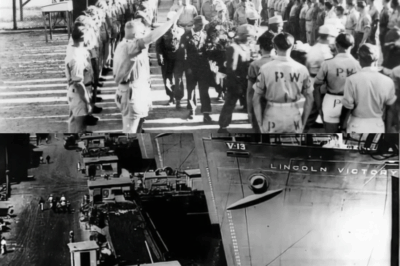

ch1 German POWs Were Shocked By America’s Industrial Might After Arriving In The United States

June 4th, 1943. Railroad Street, Mexia, Texas. The pencil trembled slightly as Unafitzia Verer Burkhart wrote in his hidden diary,…

‘There wasn’t enough room in the car, so leave her at home.’ My 6-year-old daughter left the lights on all night while they took my sister’s kids on a yacht; I didn’t cry, I pressed one button… and overnight, the family mask fell off…

My parents left my six‑year‑old daughter alone in their house for a week and went on a luxury vacation with…

End of content

No more pages to load