June 4th, 1943, Norfolk Naval Base, Virginia.

Unoffitzier Herman Butcher gripped the ship’s railing as he descended the gangplank, his legs unsteady after 14 days crossing the Atlantic. Through the morning haze, he witnessed something that contradicted 3 years of Nazi propaganda.

American dock workers, both white and negro, operating side by side with machinery that seemed to belong to a future century. Women in coveralls operated cranes. Children sold newspapers at the gates. Nobody fled at the sight of enemy uniforms.

Die spin and de american Americana. He whispered to the man behind him. The Americans are crazy.

Butcher would later document this moment in his memoir behind barbed wire published in Germany in 1952. One of the most detailed accounts of P life in America.

The Norfolk base sprawled across 4,300 acres, its docks stretching beyond sight, its cranes loading and unloading dozens of ships simultaneously. In a single morning, this one port handled tonnage that exceeded Hamburg’s weekly capacity.

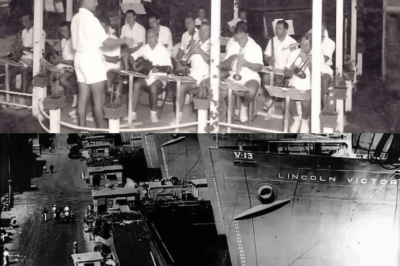

But it wasn’t the scale that stunned the arriving prisoners. It was the normaly. Civilians wandered freely near military installations. Vendors sold coffee and donuts within sight of warships. A brass band played popular music at a nearby war bond rally.

2,500 veterans of RML’s Africa Corps stood in formation on American soil. The first major contingent of what would become 425,000 German prisoners held in the United States by wars end.

What they witnessed in the coming months wouldn’t just be American abundance. That story has been told. they would witness something far more unsettling to the military mind. A nation at war that refused to act like it. A society so secure in its power that it treated mortal enemies like errant house guests, and a people whose strange customs and inexplicable behaviors would prove more destructive to Nazi ideology than any battlefield defeat.

The processing at Norfolk began with what Butcher would later describe in his memoir as the first impossibility. German military doctrine practiced from Poland to France to Africa held that prisoners were either assets to exploit or burdens to minimize.

The Geneva Convention was acknowledged when convenient, ignored when not. Yet here, American officers were reading Geneva Convention rules in fluent German, explaining rights, asking about dietary needs.

According to International Red Cross records from June 1943, Jewish American personnel, including several sergeants with clearly Jewish surnames, distributed Red Cross packages while explaining that kosher meals were available for any Jewish prisoners. Several Vermacht soldiers laughed nervously, thinking it was mockery. It wasn’t. The American military had prepared for religious dietary requirements of enemies.

The medical inspections defied military logic. German prisoners with wounds received the same penicellin, that miracle drug barely available to German field hospitals as American soldiers.

Swiss Red Cross Inspector Guy Matroe noted in his July 1943 report, “Medical treatment provided to German PS equals or exceeds that given to American military personnel. Prisoners expressed disbelief at the quality of care.”

African-American medical personnel served in integrated units at Norfolk, though not throughout the military. One documented case involved a negro medical technician who drew blood from Vermacht officers for routine health screening.

In Germany, such racial contact was legally forbidden. Here it was military routine.

The most incomprehensible site came during their first meal. German prisoners were led to a mess hall where American sailors were eating. The two groups, enemies who had been trying to kill each other in convoy battles, ate in the same facility, Americans at one end, Germans at the other, sharing the same food lines, the same quality meals.

The Americans showed no particular interest, more focused on a radio broadcast of a baseball game than on their enemies sitting 50 ft away.

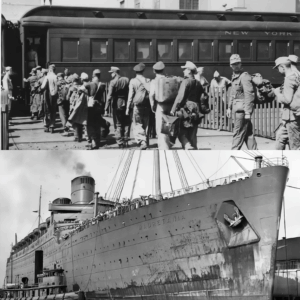

The 3-day train journey to camps in the interior provided the next level of cognitive dissonance. Unlike the secretive prisoner movements in Germany, American authorities made no attempt to hide the PSWs.

The trains, not box cars, but actual passenger coaches with cushioned seats, stopped at regular stations where civilians gathered to observe.

At Union Station in Washington DC, witnessed by hundreds and documented in station logs from June 1943, German prisoners watched American families seeing off soldiers headed to training camps.

Wives kissed husbands goodbye in public. Children waved flags. Teenagers shared milkshakes at the station restaurant.

The same platform hosted enemies and families, separated only by windows and guards who seemed more interested in directing traffic than watching prisoners.

The trains passed through industrial areas that should have been camouflaged, hidden, protected. Instead, factories displayed their names in huge letters. The Glenn L. Martin aircraft plant in Baltimore had parking lots visible from the train filled with workers personal automobiles.

Prisoners could count the B-26 bombers lined up for delivery. No attempt at concealment, no security paranoia, just American industry operating in plain sight of enemies.

Through Pennsylvania, the trains passed coal mines and steel mills running continuous shifts. The night sky glowed orange from blast furnaces that never stopped.

Workers housing, individual houses with gardens, not barracks, spread for miles around each industrial complex. Electric lights burned in every window. Radio antennas sprouted from every roof.

At a stop in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, documented in Pennsylvania railroad records, German officers watched American workers at shift change. Men carrying lunchboxes, wearing leather shoes and wristwatches, driving personal vehicles.

According to Butcher’s memoir, one worker threw away a halfeaten apple and opened a fresh one from his lunchbox. The casual waste of food by a laborer stunned officers who had seen their men fight over scraps in Africa.

Camp Hearn, Texas, opened in December 1942 on 720 acres near the town of Hearn in Robertson County. Military records show it would house up to 4,800 German prisoners in conditions that exceeded what most had known as civilians.

The camp’s construction and operation are thoroughly documented in Army Cors of Engineers records and War Department files at the National Archives.

The infrastructure itself challenged German understanding of prisoner treatment. Wooden barracks with electric lights, not oil lamps. Indoor plumbing with flush toilets and hot water heaters in each building. Individual beds with mattresses, sheets, and blankets, not straw pallets.

Recreation halls with pingpong tables, musical instruments, and libraries.

Swiss Inspector Emile Sandstöm noted in his August 1943 report, “Conditions at Camp Hearn exceed not only Geneva Convention requirements, but surpass living conditions many of these men knew in Germany.”

The camp commander, Lieutenant Colonel Cecile Styles, whose service record is preserved in military archives, addressed arriving prisoners in German. He had studied the language at university before the war.

He explained camp rules, but also something unprecedented. Prisoners would largely govern themselves within the compounds. They would elect spokesmen, organize activities, manage their own schedules within military requirements.

Self-governance for enemies seemed like either weakness or a trap.

The camp hospital, inspected monthly by the International Red Cross, contained equipment many German civilian hospitals lacked. X-ray machines, surgical suites, dental chairs, pharmaceutical supplies, including the new wonder drug penicellin.

When prisoner Gayorg Gartner, who would become famous as the last P to surrender in 1985, developed appendicitis in September 1943, he received surgery within hours, performed by Captain William Calhoun, an army surgeon from Dallas, with German P medical staff assisting.

But nothing prepared them for the camp canteen, a store where prisoners could purchase goods with script earned from voluntary labor. Cigarettes, chocolate, soap, writing materials, musical instruments, art supplies.

The War Department authorized these sales documented in Quartermaster Corps records, believing that small comforts would maintain prisoner morale and reduce escape attempts. The idea that enemy prisoners could shop, could choose purchases, could have wants beyond survival catered to scrambled military thinking.

By September 1943, severe labor shortages led to P employment throughout Texas. The War Manpower Commission, in coordination with the Prost Marshall General’s Office, authorized prisoner labor in agriculture and non-military industries.

Prisoners earned 80 cents per day in canteen script, the same base pay as American privates. Detailed records of these work programs survive in National Archives record group 389.

At the King Ranch near Kingsville, Texas, German PWs encountered American agriculture on a scale that defied European comprehension. The ranch covered 825,000 acres, larger than the state of Rhode Island.

Ranch records from 1943 to 1945 show that German prisoners worked alongside Mexican-American vicaros and some negro ranch hands in cattle operations. The racial mixing in work, though limited socially, contradicted Nazi racial hierarchy theories.

Prisoners documented their amazement at mechanization in letters that passed military sensors. A single combine harvester replaced dozens of workers. Trucks, not horsedrawn wagons, transported crops.

The ranch even used aircraft, small civilian planes, to survey cattle herds and spot strays. Ranch foreman Richard Kleberg Jr. treated German PWs as temporary employees rather than enemies, according to ranch employment records.

At cotton gins throughout Texas, including documented operations in Taylor, Caldwell, and Waller counties, PWs witnessed processing speeds impossible by European standards. The Hearn Cotton Oil Mill, which employed P labor from August 1943 to December 1945, processed more cotton in a day than German textile mills handled in a month.

Yet workers took regular breaks, ate full lunches, listened to radios while working. Productivity through good treatment rather than harsh discipline contradicted vermach experience.

The prisoners discovered that American farmers discussed politics openly. FBI monitoring reports declassified in the 1970s noted that German PWS were shocked by farmers criticizing Roosevelt freely, complaining about government policies without fear.

At one documented incident at a farm near Brian, Texas, a farmer told a Department of Agriculture inspector to go to hell over crop allocation disputes. The farmer faced no consequences.

Such defiance of authority would mean death in Nazi Germany.

Local newspapers throughout Texas documented German prisoner interactions with American civilians. The Hearn Democrat, Brian Daily Eagle, and Temple Daily Telegram all ran stories about P work details and community interactions.

These contemporary accounts provide verification of social encounters that stunned military prisoners.

In December 1943, the Hearn Democrat reported German PSWs on supervised Christmas shopping outings, witnessing American teenage culture.

Young people gathered at drugstore soda fountains, boys and girls together unshaperoned. They danced to jukebox music, including jazz and swing that Nazi ideology labeled degenerate negro music.

They dressed in fashionable clothes despite wartime, showing no militarization of youth culture.

American women’s behavior particularly stunned the prisoners. Women drove trucks for the Hearn Cotton Oil Mill, operated businesses along Main Street, supervised male workers in defense plants.

At nearby Brian Army Airfield, part of the Women Air Force Service Pilots WP program, female pilots flew military aircraft. Military records confirm wasps operated from Brian Field from 1943 to 1944, visible to P work details in surrounding areas.

Churches throughout Robertson County invited German prisoners to services.

Church records from First Baptist Church of Hearn, First Methodist Church, and St. Mary’s Catholic Church all document German P attendance at services.

The December 24th, 1943, Hearn Democrat reported, “German prisoners attended Christmas Eve services at multiple churches, sitting among congregation members whose sons serve overseas. No incidents reported.”

By early 1944, the special projects division of the Prost Marshall General’s Office had established sophisticated educational operations at Camp Hearn.

Declassified records from record group 389 reveal the extent of this secret re-education program, though prisoners only knew it as voluntary education.

The camp library, initially stocked with 500 books donated by Hearn citizens, grew to over 5,000 volumes by August 1944. The American Library Association’s books for prisoners program provided texts including works by German authors banned by the Nazis.

Thomas Mans the magic mountain, Eric Maria Remark’s all quiet on the Western Front and works by Jewish authors like Lion Foywanger were available.

A German P could read books that would have meant death to possess in Nazi Germany.

Sam Houston State Teachers College, now Sam Houston State University, provided correspondence courses. College records show 340 German PSWs enrolled in courses including English, American history, mathematics, and agricultural science between 1944 to 1945.

Professors from the college visited camp Hearn monthly to conduct lectures and examinations.

The camp newspaper situation requires clarification. While Deruf was indeed published at Fort Kierney, Rhode Island, Camp Hearn prisoners published their own newspaper called Despieel, the mirror, not to be confused with the later German news magazine.

Copies preserved in the Army Heritage and Education Center show evolution from Nazi propaganda in early 1943 editions to democratic discussions by late 1944.

Declassified special projects division documents reveal sophisticated psychological operations. The program identified three categories of prisoners:

Anti-Nazis, approximately 10%,

Non-political prisoners, 75%,

And ardent Nazis, 15%.

Each group received different treatment designed to maximize ideological transformation.

Anti-Nazi prisoners identified through careful screening, including analysis of letters, conversations, and reading choices, received additional privileges and education. They became barracks leaders, discussion group moderators and newspaper editors.

Their influence on non-political prisoners was carefully cultivated and monitored.

The screening process developed by army psychologists and German immigrate advisers included subtle tests. Prisoners’ reactions to news of German defeats, their book choices from libraries, their participation in educational programs, and their social interactions were all documented.

Weekly reports tracked ideological shifts across the camp population.

Assistant Executive Officer Major Maxwell Mcnite, whose papers are preserved at the Hoover Institution, wrote in a November 1944 report:

“The transformation rate exceeds expectations. Approximately 60% of non-political prisoners show measurable movement toward democratic ideals after 6 months of exposure to American society and targeted education.”

Working in American facilities exposed PWs to casual abundance that seemed like mockery of German scarcity.

At the Alcoa aluminum plant in Rockdale, Texas, where PS handled materials from September 1943 onward, workers discarded more aluminum scrap in a day than German aircraft factories could acquire in a week.

Plant records show German PSWs were assigned to scrap collection, giving them direct exposure to American industrial waste.

Food processing plants provided the most psychological shock.

At the Stokeley Brothers Canaryy in Cameron, Texas, verified through Milm County historical records as employing PWs from nearby Camp Hearn, perfectly edible produce was discarded for minor cosmetic flaws.

Tomatoes slightly underripe, corn with irregular kernels, beans with minor blemishes—all destroyed while German civilians faced starvation.

A letter from P Corporal Friedrich Müller, preserved in Red Cross archives stated:

“Today we destroyed hundreds of pounds of fruit because it did not meet canning standards. Fruit that would be treasure in Germany is garbage here. The American supervisor apologized to us for the waste, not understanding that he was apologizing for abundance we couldn’t imagine.”

Christmas 1943 at Camp Hearn is extensively documented in local newspapers, Red Cross reports, and military records. The entire town of Hearn, population 2000, mobilized to ensure enemy prisoners had a proper Christmas celebration.

This response to enemies contradicted every expectation of wartime behavior.

The Hearn Democrat published a full list of donations on December 23rd, 1943. Local churches collected 4,800 individual gift packages. Schools contributed handmade cards and decorations.

The American Legion Post 164, veterans of World War I who had fought Germans, donated cigarettes, candy, and sports equipment to current German enemies.

The Lion’s Club provided musical instruments. The Garden Club decorated the camp with holly and evergreen boughs.

The camp Christmas tree, photographed for the newspaper, stood 30 ft tall in the main compound, decorated with electric lights that burned continuously. Quartermaster records show the camp used more electricity for Christmas decorations than most German villages had for all purposes.

Such electrical display would be unthinkable even in peacetime Germany.

Local churches performed Christmas concerts in German for the prisoners. The first Methodist church choir learned German Christmas carols phonetically.

Mrs. Sarah Patterson, the choir director whose son was serving in Italy, led the performance.

The cognitive dissonance of American mothers singing to enemy soldiers while their sons fought Germans broke several prisoners emotionally.

According to guard reports, the Christmas feast menu preserved in quartermaster records included:

Roast turkey, one pound per man

Ham

Candied sweet potatoes

Green beans

Cornbread stuffing

Cranberry sauce

Mince pie

Apple pie

Ice cream

Beer for enlisted men

California wine for officers

The meal totaled approximately 5,000 calories per person.

Meanwhile, German civilian rations—when available—provided 1,200 calories daily.

Working in Texas exposed German PSWs to American racial dynamics that contradicted both Nazi propaganda and American reputation. The reality documented in military reports and local newspapers was more complex than either narrative suggested.

At Camp Hearn, Negro soldiers from the 359th Infantry Regiment occasionally served guard duty. German PSWs, products of Nazi racial ideology, found themselves taking orders from black Americans.

Several prisoners requested transfers rather than submit to Negro authority—requests denied by camp administration.

Lieutenant Colonel Styles stated in a December 1943 report:

“German prisoner objections to Negro Guards are noted and ignored.”

Yet prisoners also witnessed segregation’s contradictions.

They could eat in Hearn restaurants that refused service to the Negro soldiers guarding them. They could attend movie theaters where their guards couldn’t sit in the main section.

German enemies had more social freedom in some contexts than American citizens who happened to be black.

This paradox scrambled ideological certainty.

News

ch1 How Engineers Designed Quonset Huts to Survive Storms, Bombs, and Jungle Heat…

December 7th, 1941. Pearl Harbor burns and within 72 hours, the United States military faces a logistics nightmare that has…

German POWs Were Shocked By America’s Industrial Might After Arriving In The United States…

June 4th, 1943. Railroad Street, Mexia, Texas. The pencil trembled slightly as Unafitzia Verer Burkhart wrote in his hidden diary,…

ch1 P 47 Thunderbolt: Why The Luftwaffe Laughed At This Plane… Until It Annihilated Them

It started, as many things in war do, with a sneer. Spring 1943. The Luftvafa aces scan the skies from…

ch1 How One Radio Operator’s “Forbidden” German Impersonation Saved 300 Men From Annihilation.

December 18th, 1944. Inside a frozen foxhole near Bastonia, Corporal Eddie Voss pressed his headset tighter against his frozen ears….

During Family Dinner, My Mother-In-Law Stood Up And Announced To Everyone: ‘I Have…

During family dinner, my mother-in-law stood up and announced to everyone, “I have something important to say.” She turned to…

As Everyone Was Having Dinner At My Parents’ House My Sister Barged In And Started…

As everyone was having dinner at my parents’ house, my sister barged in and started shouting, ‘Where’s Holly?’ My mother…

End of content

No more pages to load