Like five currents converging into a single wave, the forces shaping late-night television have started to move in unison. What began as quiet conversations between rivals has evolved into something few thought possible — a united front of the biggest names in comedy.

For years, Stephen Colbert, Jimmy Fallon, Seth Meyers, John Oliver, and Jimmy Kimmel competed for the same hour, the same headlines, the same exhausted audiences who stayed up just long enough to laugh before sleep. They traded ratings wins and viral clips like trophies. But now, the same late-night world that once fueled their rivalry is collapsing — and those same hosts are coming together to build something entirely new.

It all began in the shadow of a scandal. After Jimmy Kimmel’s sudden suspension from ABC over controversial remarks, the network’s silence was deafening. Industry chatter suggested his era might be over, that late-night had finally found its first casualty in an age of polarization. But what no one predicted was that Kimmel’s fall would become a rallying cry — not for outrage, but for reinvention.

Behind closed doors, his friends and former competitors began reaching out. At first, the calls were about support, solidarity, maybe just sympathy. But over time, those conversations turned into brainstorming sessions. The four hosts who once fought to outdo one another began imagining what late-night could look like if it wasn’t divided by networks or formats or ratings wars.

Someone — no one seems to remember who — said it first: “What if we just built our own?”

From there, the idea took on a life of its own. Meetings followed. Private dinners. Confidential calls between agents and producers who usually kept their cards close. For the first time in decades, the biggest figures in television comedy were talking not about competition, but collaboration.

Each brought something unique to the table. Colbert, with his political intellect and command of the news cycle. Fallon, with his mainstream appeal and ability to turn chaos into charm. Meyers, sharp and relentless, with a writer’s edge that cut through spin. Oliver, analytical and global, used to building comedy out of complexity. And Kimmel — bruised, silenced, but still standing — brought what none of the others had: a story of survival.

“They realized their differences were the strength,” said one producer close to the project. “It’s like a band — every instrument matters. Alone, each has power. Together, they can make noise no network could contain.”

The format, still shrouded in secrecy, reportedly defies every rule of late-night. No permanent host. No fixed desk. Instead, a rotating dynamic — one night might feature interviews led by Colbert and Fallon; another might dive deep with Oliver and Meyers dissecting the week’s chaos. Some nights could resemble a live roundtable; others, a hybrid of sketch, music, and unscripted conversation.

The working title, whispered in development rooms and production calls, is “The Fifth Chair.”

“It’s a nod to what they represent,” said an insider. “They’re not competing for the chair anymore. They’re building a fifth one — for everyone watching.”

Timing couldn’t be more critical. The traditional late-night model is in freefall. Ratings across the major networks have dropped to record lows. Younger audiences have migrated to clips, reels, and streams, where a two-minute joke gets more traction than a full monologue. The days of a single host commanding a nation’s attention at midnight are gone.

Networks have tried everything — musical segments, celebrity games, political interviews — yet the numbers keep slipping. The audience that once stayed loyal to one show now scrolls endlessly, chasing moments, not routines.

In that chaos, this alliance isn’t just bold — it’s survival.

Insiders describe the mood inside network headquarters as panic mixed with disbelief. “If they actually pull this off, it changes everything,” said one senior executive at a rival studio. “You’re talking about five empires merging into one. The networks can’t compete with that. They built these people. Now they might lose them.”

The corporate scramble has already begun. Agents are renegotiating deals, lawyers are parsing contracts, and executives are trying to calculate what it would take to keep their stars in-house. But the power has shifted. For the first time, the comedians hold the leverage.

“They don’t need the networks anymore,” another insider said. “They need each other — and an audience that’s already waiting.”

For Kimmel, the story carries special weight. Once the target of controversy, he now stands at the center of a movement. Friends say the ordeal left him shaken, but also liberated. “He’s done apologizing,” one confidant said. “He’s focused on building something that can’t be taken away with one executive’s decision.”

Those close to the group describe a bond that’s both pragmatic and emotional. Years of competition have softened into mutual respect. Colbert and Oliver are said to share long philosophical calls about the role of comedy in a divided culture. Fallon, once criticized for avoiding politics, now embraces the chance to step outside the network mold. Meyers, ever the strategist, has become the quiet architect of the new format.

They all know the risks. Egos could clash. Schedules could implode. Networks could threaten lawsuits or block access to studio archives. But none of that seems to deter them. “It’s too late for fear,” one writer said. “The old late-night is already dead. This is about what comes next.”

If history is any guide, this alliance would be unprecedented. Late-night has always been built on singular personalities — from Carson to Letterman, from Leno to Conan. Collaboration was rare, and friendship often temporary. But this generation grew up watching the internet dismantle the very idea of exclusivity. The audience doesn’t care who “owns” a format anymore. They just want something that feels alive.

That’s what these five are betting on.

The potential reach is staggering. Collectively, they command hundreds of millions of followers across platforms. A single joint appearance could generate global buzz in minutes. Streaming services are already circling, offering budgets and creative freedom that traditional TV can’t match. “It’s not just a show,” said one studio executive. “It’s a cultural event waiting to happen.”

But not everyone is cheering. Critics warn that blending so many powerful voices could backfire. Without one anchor, the show might lose focus. Too many cooks, too much chaos. “You can’t build lightning in a committee,” one veteran producer warned.

And yet, something about this moment feels different. Maybe it’s fatigue with the sameness of late-night. Maybe it’s nostalgia for when these hosts represented humor at its most human — a laugh after a long day, a shared breath in a fractured time.

Whatever it is, the idea has momentum. And for the first time in years, late-night television — once the land of comfort and routine — feels unpredictable again.

As one insider put it, “They’re not just saving late-night. They’re rewriting what it means to be on it.”

No one knows where this will lead. The logistics alone are daunting. The creative challenges are endless. But for now, something rare is happening: five of television’s biggest competitors are stepping into the same light, not as rivals, but as architects of what comes next.

And in that fragile, thrilling moment — between collapse and creation — the future of late-night doesn’t just seem uncertain. It feels alive again.

News

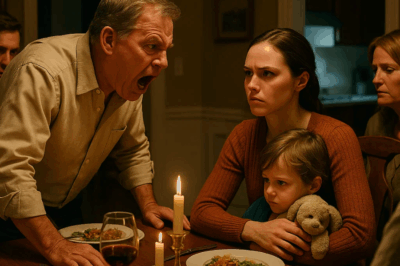

ch1 At The Family Dinner, My Dad Yelled In My Face: “You And Your Kid Are Just Freeloader’s!”…

My name’s Nina, 29, single mom to a sweet six-year-old boy named Leo.I work full time in tech, pay my…

ch1 My Parents Hosted A Fancy Family Dinner — But Told Me To Sit At The…

My name’s Elias. I’m thirty-four.And I learned the hard way that some families only value you as long as you…

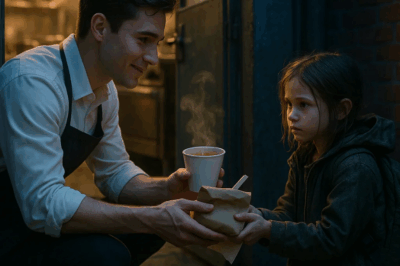

ch1 Waiter Secretly Helped a Hungry Girl! When She Pulled the Bride’s Veil at the Banker’s Wedding, No One Could Believe What Happened Next…

A Fateful Encounter: The Waiter and the Homeless Girl James, a waiter at a high-end restaurant, couldn’t shake the feeling…

ch1 “You insult me behind my back and then ask me for money?” — my relatives never realized I was standing right there, hearing every word.

Marina had always been proud of her career. A good position, a high salary, the respect of her colleagues—she had…

ch1 “You insult me behind my back and then ask me for money? ” — my relatives had no idea I’d overheard their conversation…

Marina had always been proud of her career. A good position, a high salary, the respect of her colleagues—she had…

POLITICAL FIRESTORM: GOP SPOKESWOMAN BLASTS NFL OVER BAD BUNNY’S SUPER BOWL HEADLINE — “OUT OF TOUCH WITH AMERICA!” 😱🔥 The NFL’s decision to put global superstar Bad Bunny front and center at Super Bowl LIX has unleashed a nationwide debate. Karoline Leavitt’s sharp rebuke ignited a social media war — one side praising inclusivity, the other crying cultural betrayal. What was meant to be a halftime celebration has become a flashpoint in America’s ongoing culture war 👇👇👇

It was supposed to be an easy win for the NFL — a global headline, a modern statement, a performance…

End of content

No more pages to load