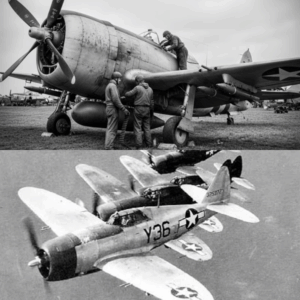

It started, as many things in war do, with a sneer. Spring 1943. The Luftvafa aces scan the skies from their perched briefings in France and Holland. Sharpeyed beneath the brim of Shermiten. The rumor mill is buzzing. America is sending something new. German intelligence photos circulate around mesh halls. A stubby barrel-chested fighter bigger than any seen before. The P-47 Thunderbolt.

Pilots snort. They call it Dare Iimer, the bucket. And soon the bathtub with wings. To them it looks less like a fighter and more like a clumsy mistake foisted by American industry. Overbuilt, overweight, not to be feared. In the bars of occupied Europe, even British Spitfire veterans raise eyebrows. Surely, one mutters, the Yanks can’t be serious.

On Allied airfields, doubts bubble up, too. Pilots trained on nimble P40s and Spitfires eye the new Republic aviation monster with awe and skepticism. Its Prattton Whitney R2800 double Wasp radial engine dwarfs its airframe. The cockpit sits high above massive cowlings. Feels like flying your grandmother’s refrigerator, cracks one Mustang pilot on his first encounter.

The jug, they call it, partly for its shape, partly for the juggernaut they are told it will become. But not yet. It’s not just size. The first hard stats trickle in. A maximum takeoff weight of eight tons, a wingspan broader than a Messor Schmidt, eight heavy 50 calibers, but a reputation for poor climb and tricky handling at low altitude.

Engineers love its power plant and advanced turbo supercharger, but pilots grumble about its long takeoff roll, sluggish stick, and the kind of cockpit heat that wilts a man before the action even starts. Even in US Army Air Force training, the instructors admit in a turning fight with a BF- 109 or FD-190, the new P47 is in trouble, at least on paper.

Luftwafa veterans watch from cloud cover above the channel. The first thunderbolts they encounter rarely chase, sticking to altitude, failing to turn inside German interceptors. Among the seasoned BF- 109 drivers, dives are met with taunts, head-on passes with bravado. Go after the big ones. You’ll nail them before they can haul those fat bellies around, says one group in common. And laughing, his unit complies.

Early Luftwaffa kill reports describe thunderbolts as easy targets when separated from their formations. But the Germans aren’t seeing the full truth. They’re only catching the P-47 on its first awkward laps. The real test lies ahead.

In the daily grind of escorting bombers to the heart of the Reich, and in the first bloody encounters over the railyards of France and the forests of Belgium, the Thunderbolts real strengths—raw speed, brutal firepower, and ruthless survivability—are about to rewrite every joke, every assumption, and every rule in the sky. The battle for air supremacy is about to shift.

Laughter is about to turn to disbelief, then to terror, and the jug will take its place as the most feared hammer of Allied air power. The P47 Thunderbolts transformation from laughingstock to legend unfolds in thunderclap bursts across Europe.

Summer 1943. Bombers stream snake toward occupied France and Germany. Fortresses of steel and aluminum glinting through high contrails. Escorting them first to 10,000 ft, then to 20, then to 30 are wings of P47s. Their radial engines bellow. Turbo superchargers whine.

Luftwafa ground observers report strange giants overhead. Too big to outturn perhaps, but unstoppable in their headlong dives. The first real shock comes on July 30th, 1943. Eight Air Force thunderbolts led by Zemp’s Wolfpack tangle with BF 109s near Mden. At altitude, German pilots are caught by surprise.

The P47’s turbocharging finally shows its teeth, giving it unmatched speed and power above 25,000 ft. Climbing for the bombers, Luwaffa fighters find themselves hounded by thunderbolts swooping out of the sun, hitting, climbing, rolling away. An ace named Hines Bear would later confess, “I could hit it a dozen times, but the big bird simply took the blows and kept coming. To shoot one down often meant crippling its engine or hitting the pilot. Hitting the airframe alone did nothing.”

On the ground, crews marvel at damaged jugs limping home. Wings stitched with cannon fire, cylinders blown clean off, oil streaking the length of the fuselage. Yet the ship lands, pilot alive, machine ready for repair instead of a grave. The jug’s radial engine and robust armor are not a designer’s conceit, but a pilot’s best friend.

Unlike the slender, liquid cooled Mustangs or Spitfires, the Thunderbolt shrugs off hits that would doom lesser planes, refusing to fall from the sky. German tactics are forced to adapt. At first, interceptors stay away, trying only to pick off stragglers or lure the jugs to lower altitudes.

But slowly, the Luftwaffer realizes at speed and altitude, the bathtub is lethal. American pilots begin to master boom and zoom attacks, diving with crushing force, blasting through targets with 850 cal machine guns, then climbing away before enemy cannon find their mark.

Ground crews whisper about P47s returning from six-on-one dog fights with all but a paint scratch. Worse for the Luftwaffa, the Thunderbolts range and firepower keep growing. Drop tanks appear under the wings. Missions hit deeper. Escorts now reach close to the ruer.

By autumn, German air defense posts warn, “Do not underestimate these aircraft. Engage with caution.”

When the thunderbolts descend as fighter bombers, rockets under wing, bombs on the fuselage. They slice railways, bridges, fuel convoys, and troop columns across the continent, leaving tangled iron and smoke in their wake. For every Luftvafa ace boasting a thunderbolt kill, the toll is steep.

American losses are often from ground fire or engine failure, not enemy fighters. The survivors return again and again, veterans growing bolder, wolfpacks hunting in teams through the battered skies of France and Belgium.

As the Jug’s legend grows, so too does its deadliness. The Luftwaffa’s laughter is replaced by tur briefings, hurried tactics, and a name spoken with weary respect. Thunderbolt. Heavy, yes, but if it gets the first strike, it will kill you.

By the summer of 1944, the Thunderbolt strength had shifted the very nature of air warfare. What began as jokes about the bathtub with wings evolved into curses whispered by every German soldier unlucky enough to be caught in its path.

The P-47 had proven itself as a dog fighter at high altitude. But its true legend would be forged at treetop level, battering the Axis war machine into submission across France, Belgium, and Germany itself.

In the weeks ahead of D-Day, P47 squadrons prowled the skies, seeking out every conceivable target that could move Germany’s legions. Eight huge machine guns laid down streams of 50 caliber fire, but now their wings bore even deadlier loads: bombs, unguided rockets, napalm canisters.

The jug could carry up to 3,000 lbs of ordinance, nearly half that of a B17 Flying Fortress on a shorter mission. Thunderbolts swooped low on railway yards, skipping bombs under bridges with heartbeat timing. They fired high velocity rockets into troop convoys.

German tank columns protected by flack found their armor pierced by armor-piercing projectiles or bombs set to detonate just above the ground. Farmers and French partisans alike watched in awe as wave after wave of jugs shredded the iron arteries of Nazi logistics.

86,000 railroad cars, 9,000 locomotives, 6,000 armored vehicles, and 68,000 enemy trucks would be claimed by Thunderbolt pilots before wars end.

On the 29th of July 1944, during the breakout near RNI, thunderbolts of the 405th Fighter Group earned their grim place in military lore. With the German 7th Army trapped in a column of tanks, trucks, and horse carts, the P-47s attacked relentlessly for more than 6 hours.

When the smoke cleared, 66 tanks, more than 200 other vehicles, and the last illusions of German ground mobility had been erased from the map. The Luftvafa, once the proud master of close air support, could not match the scale or violence of the Thunderbolt.

FW190s and BF 109s were too vulnerable at low level, their frames too fragile, ammunition too light, engines too delicate. German troops called in stookas when they could, but the mighty G87s fell to thunderbolt guns by the hundreds.

Now it was the Americans whom the weremocked feared most, with columns halting in daylight and movement shifting to the cover of night to avoid the jug’s wrath.

Ground crews marveled at their battered mounts. Dent, burn, or shred a P47. It might still limp home. Pilots returned with tails shot off, wings slit to the spars, engines coughing to the last yard of runway. More than one jug brought its pilot home with an entire cylinder blown away or with bomb racks still attached and control surfaces in tatters.

The Luftwafa’s few remaining fighter groups tasked with stopping these juggernauts suffered appalling losses. Bitter German officers noted that the only way to defeat a Thunderbolt is to catch it on the ground. In the air, it is a fortress.

Groups who laughed two years before now briefed in whispers, “Beware the P-47. Its guns are death, its pilot unafraid.”

It was in these ground attack strikes where precision met fury and steel met steel on the roads of France, the Ardens, and the Rhineland that the Thunderbolt and American tactical air power would rewrite the rules of modern warfare and help hammer out the end of Hitler’s Reich.

Mission after mission, the P47 Thunderbolt not only rewrites the rulebook for Allied tactics, it leaves a battlefield legacy etched in cold statistics and hot steel. The Jug becomes the unsung killer of the Luftwafa. Its numbers a testament to both American industry and frontline resilience.

By 1945, the P47 has flown over 746,000 sorties, more than any other US fighter. In these, it destroys 11,878 enemy planes, roughly half in the air, half on the ground, 160,000 military vehicles, over 9,000 locomotives, and 86,000 trucks.

The numbers dwarf those of the Mustang and Spitfire when it comes to ground targets. On some missions, Thunderbolts drop over 132,000 tons of bombs, nearly equaling the entire payload of medium bomber wings. It endures through 1.5 million hours of combat, using up 135 million rounds of 50 caliber ammunition.

Pilots and their ground crews see the impossible daily. Jugs coming home on five cylinders, wings slashed open, tail sections shredded by flack, yet landing intact, pilots alive and eager to rearm. The loss rate proves the legend. A mere 0.7% per mission, a figure owed as much to design as to skills at the stick.

Crews and pilots report astonishing tolerance for damage. One AC’s jug returns on only half its engine cylinders. Another lands with four feet of tail missing. Luftwafa aces, many of them survivors of the early war glory years, speak in decisive tones about the thunderbolt after 1944. It could absorb an astounding amount of lead and had to be handled very carefully, recalls German ace Hines Bear.

Far from easy prey, the jug has become a monster. Out claiming German fighters at altitude, outdiving when pursued, and unlike most, almost always giving its pilot a chance to bail or escape, even mortally wounded. The 56th Fighter Group, the eighth Air Force’s last P-47 hold out, refuses to switch to Mustangs and becomes the top scoring American group in aerial victories.

Claiming 677 enemy aircraft in the air, 311 more on the ground and losing only 128 of their own. Rival pilots take note. The Luftwaffa’s interception rate drops, attacks on bombers fail more often, and pilots are given explicit orders. Avoid thunderbolts if you value your life.

Flack batteries reeling from the loss of so many tanks and trains shift focus. Many crews spending sleepless weeks devising new camo and movement schedules to hide from the jug’s relentless hunt. The postwar years are full of memoirs, reunions, and debates. But universally, the tale is the same.

The Thunderbolts ugly airframe, mocked and derided, became the last thing many Axis crews ever saw, and the first hope for countless Allied troops on the ground, strafed and battered, but always moving closer to victory. For every pilot who flew one home, and every soldier who looked up and saw its looming bulk between him and death, the jug was more than a machine.

It was deliverance forged in laughter, rebuilt in blood, and finally in both the record books and trenches, made immortal by fire. Through thousands of missions, the myth forged by statistics found its deepest truth in those who flew the jug through European storms, desert heat, and Pacific monsoons.

Every Thunderbolt pilot who survived wrote a personal tale of terror, triumph, loss, and occasionally improbable mercy. Robert S. Johnson’s story became folklore among fighter pilots. On June 26th, 1943, his Thunderbolt was riddled by 21 cannon shells and more than 100 machine gun hits.

Wounded and nearly blinded by oil and shrapnel, Johnson flew his dying P47 back towards England. Pursued by a relentless FW190 who emptied his guns, shook his head at the still flying wreck, and saluted before peeling away. Johnson’s Thunderbolt engine seizing somehow landed. Engineers lost count at 200 bullet holes.

The morale boost and shock waves of that day resonated from briefing rooms to Luftwaffer reports. Ed Katril, leading missions during the Battle of the Bulge, destroyed Tiger tanks under fire only to find himself limping home at 120 mph, engine coughing, P47 riddled with holes, only to be escorted to Allied lines by two BF 109s who, in a rare act of chivalry, let him land safely.

Good luck and God bless, they signaled. Ed brought the battered jug back, lived and told the story for generations. Some pilots like Wally King and William Gorman faced what seemed like suicide, strafing flack batteries ahead of airborne assaults, coming home caked with flack fragments and fuel, praying for rescue with every landing.

The loss rate was still merciless, but the jug offered more second chances per bullet than any machine in the Allied arsenal. On the ground, soldiers cheered at the approach of thunderbolts. Accounts from Normandy, the Ardens, and Germany recount columns halted, tanks hiding, bridges left unguarded in daytime for fear of the jug’s shrieking death.

To the German infantry and tankers, the flying milk bottle became a nightly dread. Its 850s raking trains, columns, horse carts, and even panicked defenders and panzers who had once laughed at its silhouette.

German aces like Adolf Galland and Hines Bear, who once mocked the Jug, were later quoted expressing terrible regret underestimating the Americans bathtub, recognizing that the P47’s mixture of firepower, speed, and supercharged survivability and its pilots relentless aggression gave the Allies a decisive edge.

The legacy lived on. P47s transferred to France, Italy, Brazil, and even postwar Germany trained new generations of pilots. Pilots like Ed Catrell, reflecting at age 101, simply said, “I kissed the ground every time I climbed out. The thunderbolt gave me my life, and I owe everything to its steel and the men who built and fixed her.”

The laughter that once echoed in Luftwaffa barracks faded into haunted memory. Replaced by raw respect on both sides, the P-47 Thunderbolt, the jug, transformed not just the air war, but the fate of thousands. In every battered, oil stained fighter that rolled up to a hanger, Allied victory had a profile, a sound, and a soul forged in thunder.

News

German POWs Were Shocked By America’s Industrial Might After Arriving In The United States…

June 4th, 1943. Railroad Street, Mexia, Texas. The pencil trembled slightly as Unafitzia Verer Burkhart wrote in his hidden diary,…

ch1 How One Radio Operator’s “Forbidden” German Impersonation Saved 300 Men From Annihilation.

December 18th, 1944. Inside a frozen foxhole near Bastonia, Corporal Eddie Voss pressed his headset tighter against his frozen ears….

During Family Dinner, My Mother-In-Law Stood Up And Announced To Everyone: ‘I Have…

During family dinner, my mother-in-law stood up and announced to everyone, “I have something important to say.” She turned to…

As Everyone Was Having Dinner At My Parents’ House My Sister Barged In And Started…

As everyone was having dinner at my parents’ house, my sister barged in and started shouting, ‘Where’s Holly?’ My mother…

THE GUARD ASKED FOR ID. MY DAD HANDED OVER HIS RETIRED CARD. SHE’S WITH ME, HE SAID. JUST A CIVILIAN

The guard asked for ID. My dad handed over his retired card. “She’s with me,” he said. “Just a civilian.”…

MY SON SENT ME A BOX OF HANDMADE BIRTHDAY CHOCOLATES. THE NEXT DAY, HE CALLED AND ASKED SO…

My son sent me a box of handmade birthday chocolates. The next day, he called and asked, “So, how were…

End of content

No more pages to load