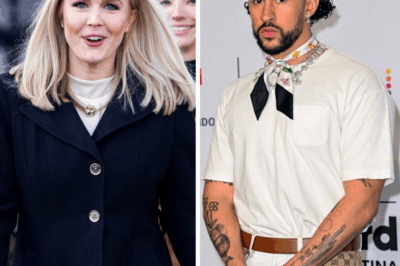

It was supposed to be an easy win for the NFL — a global headline, a modern statement, a performance to match the scope of the Super Bowl itself. The press release hit the wires at sunrise: Bad Bunny, the Puerto Rican superstar who’d conquered Spotify, fashion, and the Grammys, would headline the 2026 Super Bowl Halftime Show in Los Angeles. The words “diversity,” “inclusion,” and “global unity” pulsed through every line of the announcement like a brand campaign in motion.

But within hours, celebration turned into confrontation.

Karoline Leavitt — the fiery Republican strategist known for turning cultural flashpoints into political thunderclaps — took to X with a single sentence that would ignite the country:

“The Super Bowl is supposed to represent America — not an international playlist.”

Ten words, one cultural explosion.

Cable news picked it up by noon. By nightfall, hashtags had taken over both sides of the divide. One camp praised the NFL for “finally embracing the world.” The other accused it of “abandoning its roots.” Leavitt became the face of the backlash — young, articulate, and unafraid to frame her critique as something bigger than music.

“This isn’t about Bad Bunny,” she told Fox’s prime-time host that evening. “It’s about what the NFL stands for. Are we celebrating the American spirit, or are we apologizing for it?”

Her message hit at a moment when cultural fatigue was already high — when words like “representation” and “tradition” had become political landmines. The Super Bowl, once a unifying ritual, suddenly looked like the newest battleground in America’s identity war.

For the NFL, this was all predictable. Bad Bunny is not just a performer; he’s a phenomenon. His tours sell out faster than tickets can print. His fanbase spans continents. To the league’s executives, he represented the kind of borderless energy that keeps the Super Bowl globally relevant. “He’s the sound of the modern world,” one insider said. “And the Super Bowl is no longer just for one country — it’s for everyone watching.”

But not everyone agreed that was a good thing.

To millions of viewers who grew up watching Bruce Springsteen, Tom Petty, and Beyoncé turn halftime into cultural theater, the Bad Bunny announcement felt like a pivot — away from Americana, toward algorithmic appeal. For them, Leavitt’s critique wasn’t hate; it was heartbreak. The feeling that something familiar, something sacred, was slipping away under the weight of global branding.

On social media, the clash spiraled into something deeper — memes, music remixes, dueling edits of Leavitt’s clip spliced over Bad Bunny performances. One viral post summed it up:

“He’s singing in Spanish, she’s shouting in English — and somehow, they’re both arguing about who owns America.”

By midweek, think pieces filled the digital airwaves. The Atlantic called the controversy “a culture war in 4/4 time.” Rolling Stone argued the NFL was “finally stepping into the world it pretends not to fear.” And The Wall Street Journal warned that “turning halftime into a referendum on identity may cost more fans than it gains.”

Leavitt, meanwhile, leaned into the spotlight. Her podcast episode titled “Whose Game Is It Anyway?” racked up record downloads. She painted herself as the lone defender of cultural authenticity, accusing the league of chasing applause abroad while alienating its base at home. “They call it inclusion,” she said. “I call it erasure.”

And yet, beneath the noise, there’s a strange symmetry to it all. Bad Bunny, an artist who defies definition — masculine and flamboyant, Latin and global, pop and protest — now finds himself the symbol of everything America is fighting about: who belongs, who decides, and who gets to represent the future.

When he finally walks onto that stage next February, flanked by dancers, lights, and a billion eyes, the performance will mean more than music. It will be a mirror — one reflecting the tug-of-war over identity that defines this moment in American life.

Leavitt will likely respond in real time, her words dissected by fans and pundits alike. The NFL will count the viewership numbers. Advertisers will measure engagement. And somewhere between the spectacle and the spin, the truth will linger: that the Super Bowl, once America’s simplest joy, has become its most revealing argument.

Because this isn’t just about who sings at halftime.

It’s about who gets to speak for America — and whether that voice still sounds the same.

News

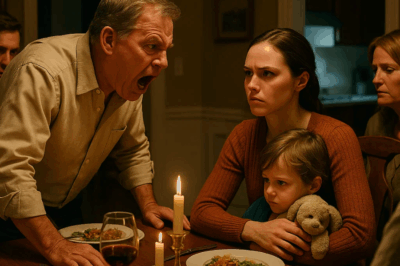

ch1 At The Family Dinner, My Dad Yelled In My Face: “You And Your Kid Are Just Freeloader’s!”…

My name’s Nina, 29, single mom to a sweet six-year-old boy named Leo.I work full time in tech, pay my…

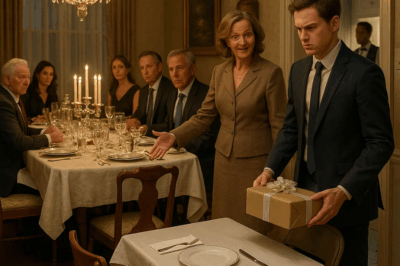

ch1 My Parents Hosted A Fancy Family Dinner — But Told Me To Sit At The…

My name’s Elias. I’m thirty-four.And I learned the hard way that some families only value you as long as you…

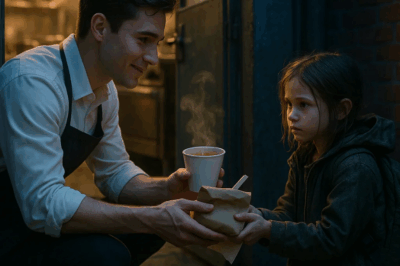

ch1 Waiter Secretly Helped a Hungry Girl! When She Pulled the Bride’s Veil at the Banker’s Wedding, No One Could Believe What Happened Next…

A Fateful Encounter: The Waiter and the Homeless Girl James, a waiter at a high-end restaurant, couldn’t shake the feeling…

ch1 “You insult me behind my back and then ask me for money?” — my relatives never realized I was standing right there, hearing every word.

Marina had always been proud of her career. A good position, a high salary, the respect of her colleagues—she had…

ch1 “You insult me behind my back and then ask me for money? ” — my relatives had no idea I’d overheard their conversation…

Marina had always been proud of her career. A good position, a high salary, the respect of her colleagues—she had…

BREAKING CLASH: NFL’S CHOICE OF BAD BUNNY FOR SUPER BOWL HALFTIME SHOW IGNITES POLITICAL FIRESTORM 🔥 Moments after the NFL confirmed that LGBTQ+ Latin megastar Bad Bunny would headline the Super Bowl LIX Halftime Show, conservative spokesperson Karoline Leavitt slammed the decision as “out of touch with American fans.” Supporters say it’s a bold step toward diversity, while critics accuse the league of alienating its core audience for global appeal. As the debate rages on, one question echoes across America: is this progress — or provocation? 👇👇👇

It began like every other corporate announcement — a polished press release, a few aspirational buzzwords, and a flood of…

End of content

No more pages to load